Archiving Retention by Dhia Dhibi

Photos by William John Brooks

Dhia Dhibi is a Tunisian multidisciplinary artist, curator, and researcher whose practice examines the intersection of art and technology. Trained initially as a three dimensional digital artist, he expanded his profile through a research master’s degree in art theory and postgraduate studies in curatorial practices. His work investigates how digital technologies shape perception, behavior, and social structures, with particular attention to Tunisia and the broader SWANA region, and this critical orientation informs his artistic, curatorial, and research activity.

Digital traces produced during moments of political rupture are simultaneously abundant and unstable. They circulate rapidly, accumulate unevenly, and remain vulnerable to deletion, account deactivation, content flagging, and the quiet attrition produced by changing devices and formats. Archiving Retention, a mixed media installation developed during the Emerging New Media Artists Programme at Diriyah Art Futures and exhibited in CONTINUUM 25, stages this condition by translating elements of the Tunisian revolution of 2010 to 2011 into a tactile archival environment composed of cabinets, drawers, and media carriers associated with older regimes of storage and retrieval. Rather than proposing an uncomplicated return to analog stability, the work functions as a critical apparatus that tests how memory is externalized, how evidentiary claims are stabilized, and how historical meaning is negotiated when the primary record is constituted by platform circulation and its associated modes of disappearance.

A useful conceptual distinction is that between data and trace. Data denotes information that can be copied and processed with minimal attention to the circumstances of inscription, while a trace retains marks of encounter, risk, and mediation. In the setting of social platforms, a trace is never separable from the infrastructure that determines capture quality, compression, upload, visibility, and retrieval. Archiving Retention foregrounds this inseparability by treating pixelation, low fidelity imagery, and raw audio not as deficiencies awaiting technical repair, but as historically specific forms shaped by unequal access to devices and networks. The installation’s emphasis on documentation made by ordinary participants counters the expectation that historical authority must originate in institutional media, while also raising a harder question: how do uneven conditions of capture later become uneven conditions of recognition.

The project frames these problems through an explicit engagement with Bernard Stiegler’s concept of tertiary retention, understood as the externalization of memory and knowledge into technical supports that organize what can be recalled and how. Externalized memory is never neutral because it selects, formats, and temporizes access. Platform architectures intensify these dynamics by binding retention to attention and ranking, such that persistence is not identical to significance. Archiving Retention responds by relocating social media remnants into a fictional museum like archive that is browsable and examinable through manual, slowed engagement. Through drawers, dossiers, and playback devices, the work reorganizes the temporality of encounter, replacing the rapid consumption typical of feeds with the interpretive labor of searching, opening, listening, and comparing.

The installation is structured through three sections, videos, posts, and sounds, each presenting focal elements that expose how mediation shapes access to events and how archival categories shape subsequent interpretation. This division is not merely a taxonomy of media types. It is an inquiry into distinct temporalities of witnessing. Video indexes duration, movement, and proximity, posts index coordination, rumor, and affective address, and sound indexes collective rhythm and crowd formation. By separating these registers while keeping them within one cabinet based system, the work suggests that revolutions are not only recorded; they are also organized, narrated, and sonically inhabited, and each mode leaves a different kind of residue.

In the videos section, the first focal element is a three dimensional printed concentric pyramid composed of twenty nine circular layers, each corresponding to a day of the uprising, with diameters that increase to reflect the growth of documentation. The piece is motivated by the semantics of the word revolution as both systemic change and cyclical movement, and it formalizes this tension by placing a linear chronology into a circular geometry. The installation translates the archive into tangible form through a process that mirrors archaeological low relief techniques: each video thumbnail is converted into a height map that generates an embossed plane. This conversion is methodologically consequential because it treats the image not only as representation but as relief structure, aligning compression artifacts with an archaeological imagination of stratification. The viewer encounters accumulation as volume, and volume as an interpretive demand. More documentation does not yield immediate clarity; it yields the obligation to sort, situate, and judge.

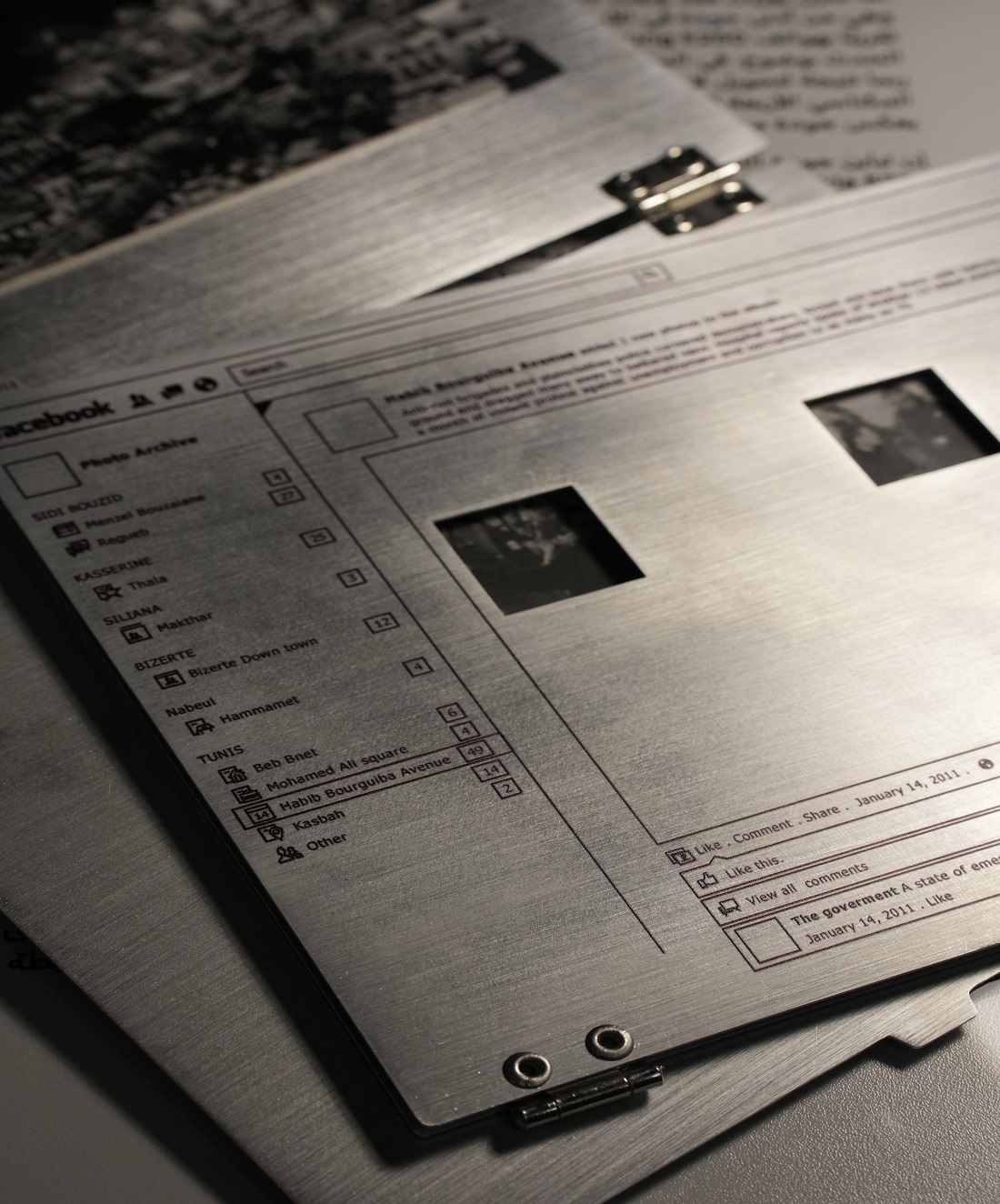

The second focal element in the videos section consists of regional maps that categorize videos by seven key areas, including Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, and Tunis, with additional sites listed as Nabeul, Sfax, Bizerte, and Gabes. Here the installation makes a pointed claim about the politics of visibility. Variations in the quality and quantity of recordings reflect socioeconomic disparities because access to recording technology depends on financial capacity. By juxtaposing layered topographic cutouts with phone models assigned through an analysis of metadata, and by adding textual annotations about social class and propagation routes, the work constrains interpretation by embedding an account of how evidence becomes available in the first place. This constraint matters because post hoc historiography can misread evidentiary density as historical importance, when it may instead index infrastructural privilege.

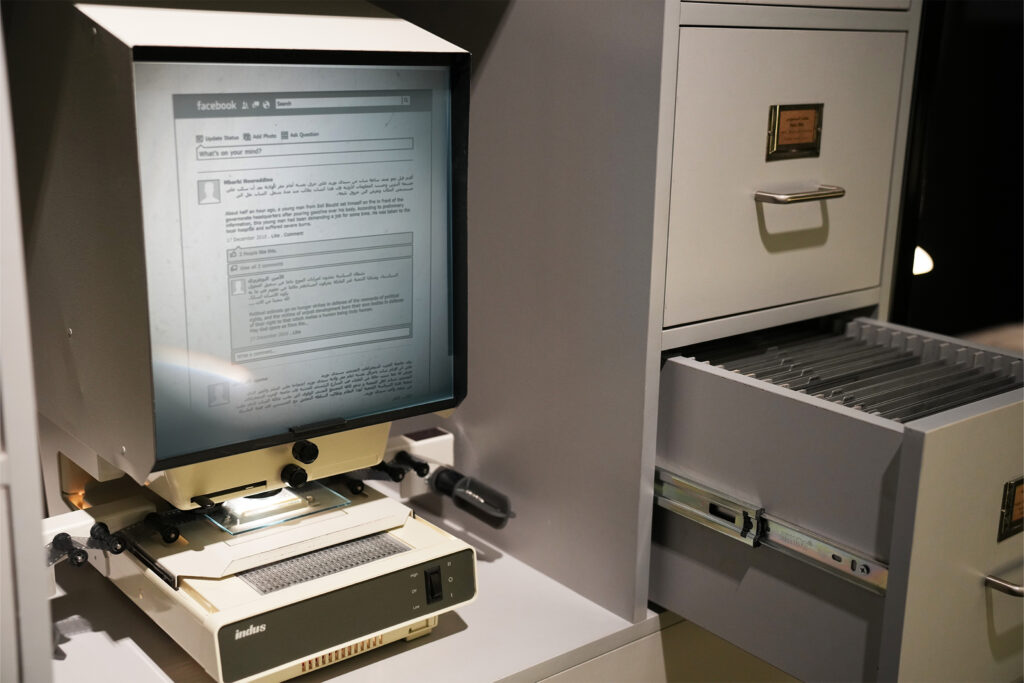

The posts section addresses a different dimension of archival instability: interface as a condition of intelligibility. Facebook status updates that facilitated decentralized protest organization are preserved on microfilm, and the viewer manually scrolls through the reel using a reader. This choice produces a temporal distortion that is conceptually central. It forces attention to the bodily habit of scrolling and reveals that the platform feed is not only a neutral container but a pedagogy of perception. Manual microfilm reading makes legibility dependent on effort and orientation, reintroducing scarcity and duration into a domain typically defined by speed and excess. The posts are no longer encountered as endlessly replaceable items in a stream, but as traces that require time to be reassembled into meaning.

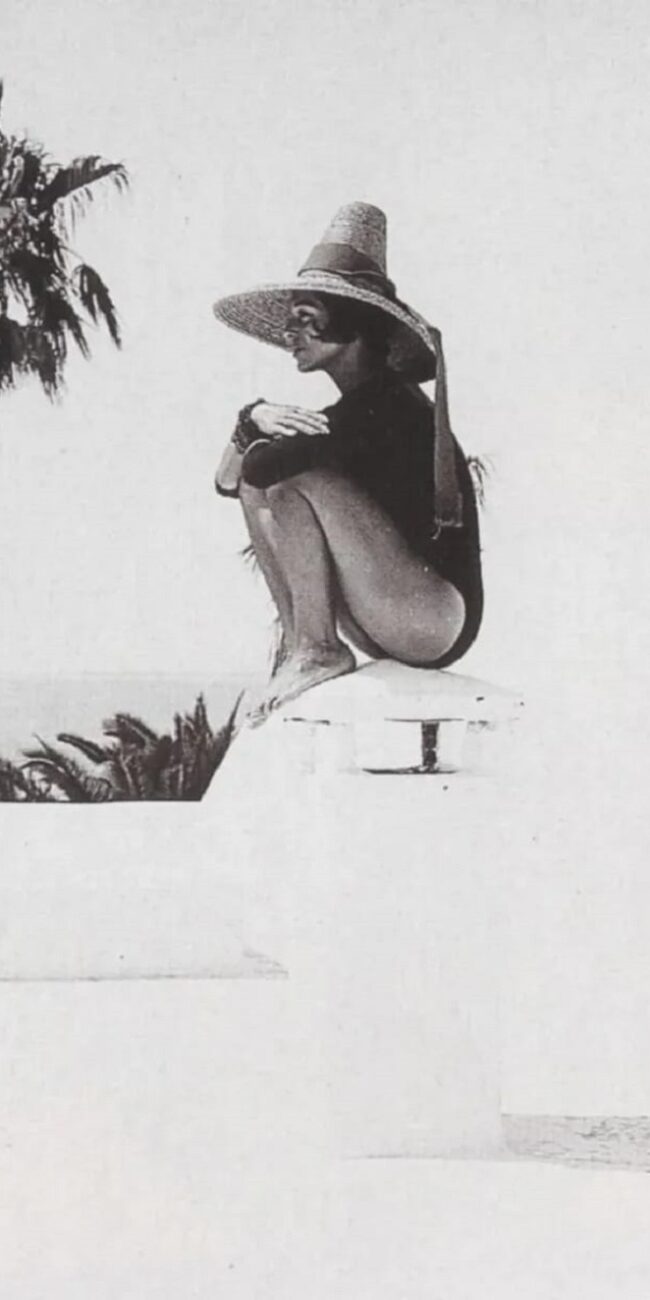

A second element in the posts section consists of archival files containing developed analog photographs detached from their original digital context, with low resolution that mirrors fragmented personal recollection. Only when placed within a simulated Facebook interface do they regain their contextual relations. This oscillation between decontextualized image and interface framed image sharpens an epistemic point: context is not supplemental to content but constitutive of what a trace can plausibly claim. Images circulating alone are vulnerable to misattribution, temporal drift, and rhetorical repurposing. By materializing the interface as a recoverable frame, the installation implies that archiving social media should preserve the conditions of address and reception, not merely the file.

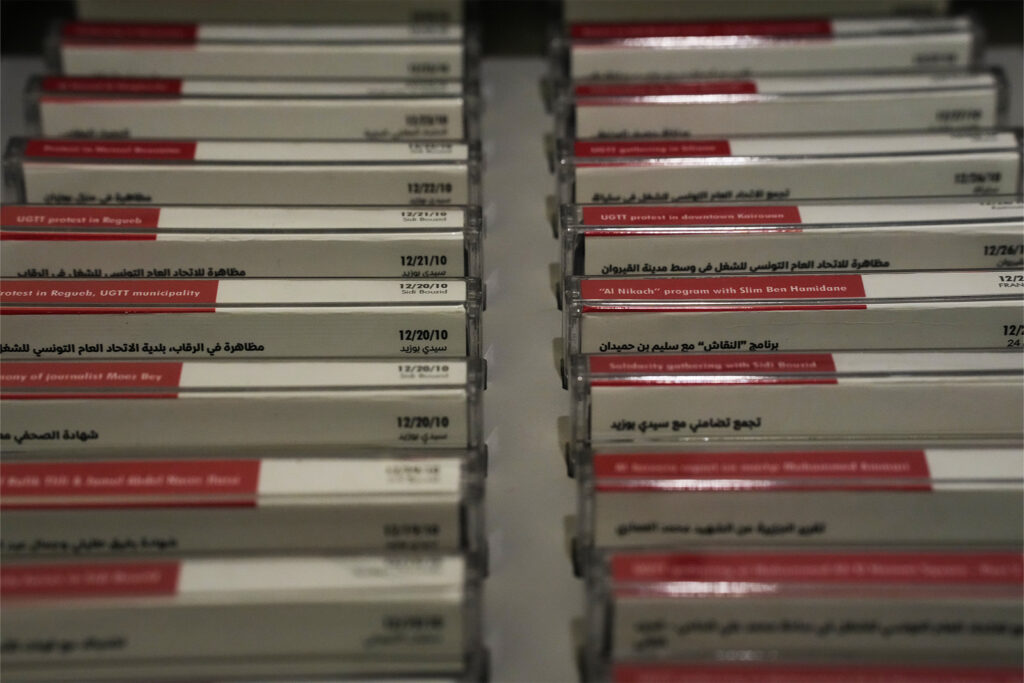

The sounds section extends these arguments into the sonic domain. It begins with a vinyl record that contains an amateur song documenting the burning of a police station in Menzel Bouzaiane, and it places this recording into a listening environment that treats sound as both document and participant in collective action. The adoption of vinyl is not a simple gesture toward durability. It reveals how archival value is performed through format, because vinyl implies deliberate listening and curated preservation in a way that compressed audio shared online often does not. Adjacent to the vinyl are cassette tapes that preserve protest slogans and anthems, organized by duration, region, and date, forming a layered sonic archive that acknowledges ephemerality while insisting on the historical weight of chant, rhythm, and repetition. Deterioration and noise become part of the record, not as romantic patina but as an inscription of the material vulnerability of memory.

Across these elements, Archiving Retention positions the archive as an archaeological problem. The project draws on the work of Tunisian researchers and historians who collected digital content years after the events and assembled an archive in 2019, encountering deactivated accounts, deleted or flagged posts, and abandoned phones. Archaeological metaphors are not decorative here. Archaeology is a discipline of inference from incomplete remains, and it treats absence as meaningful evidence of loss, destruction, and selective survival. In a platform environment, absence can be produced by moderation, policy shifts, user fear, or technical decay. By presenting the collected media within a museum like cabinet system, the installation makes retrieval uncertain and laborious, insisting that historical knowledge from digital traces is always reconstructed under constraints.

A central implication is that archiving is itself political. To archive is to decide what deserves retention, under which categories, with which metadata, and for which imagined public. Platform governance often makes these decisions implicitly, according to priorities that may clash with historical stewardship. The installation counters this by prioritizing grassroots content over institutional sources and by revealing how social media architecture can be translated into a physical archive that changes the pace of consumption and the ethics of attention. The work does not claim to resolve authenticity or completeness, and it does not conceal the partiality of the record. Instead, it makes partiality the condition of interpretation, and it asks viewers to treat the archive as a field of contestation rather than a neutral repository.

A plausible counterargument is that the materialization of digital traces risks conferring undue legitimacy through the aura of the artifact. Cabinets, dossiers, microfilm, vinyl, and cassettes can evoke institutional authority and suggest evidentiary stability even when the underlying content remains contested, fragmentary, or ethically sensitive. Moreover, any translation from platform circulation to exhibition entails curatorial selection that could re center authorship and shape narrative emphasis. These concerns are especially acute when archival work touches identifiable individuals and politically charged events. Archiving Retention counters this risk not by claiming neutrality but by foregrounding the very processes that destabilize preservation, including obsolescence, deletion, and uneven access to technology. In this way, it turns the authority of the museum like setting into a question rather than an answer.

A second counterargument concerns decontextualization. Extracting posts and media from social platforms can sever them from the dialogic ecology of comments, shares, and networked reception through which meaning was generated. Even a simulated interface cannot fully reconstruct the social relations that once surrounded a post. The installation responds by making context a visible problem. It requires a practice of recontextualization through manual browsing and comparison, thereby training the viewer to recognize that historical interpretation is not retrieval alone but a disciplined reconstruction of relations among traces. The work’s insistence on effort, spanning microfilm scrolling, drawer searches, and playback, positions historical understanding as a form of responsibility rather than consumption.

In synthesis, Archiving Retention advances an account of political memory under conditions of perpetual content creation and accelerated circulation. It argues that digital evidence is neither automatically durable nor automatically interpretable, and that the survival of traces is shaped by infrastructure, inequality, and platform governance. By translating social media remnants of the Tunisian revolution of 2010 to 2011 into a hybrid cabinet based archive, the installation does not simply preserve a past. It reconditions the terms under which that past can be encountered, evaluated, and debated, shifting attention from the volume of traces to the ethics and politics of their retention. Its ultimate claim is that the future of collective remembrance depends not only on storing files, but on designing forms of access that remain attentive to technological decay, contextual loss, and the unequal circumstances under which evidence is produced.