More Than a Decade Missing: The Silence Around Chourabi and Ktari

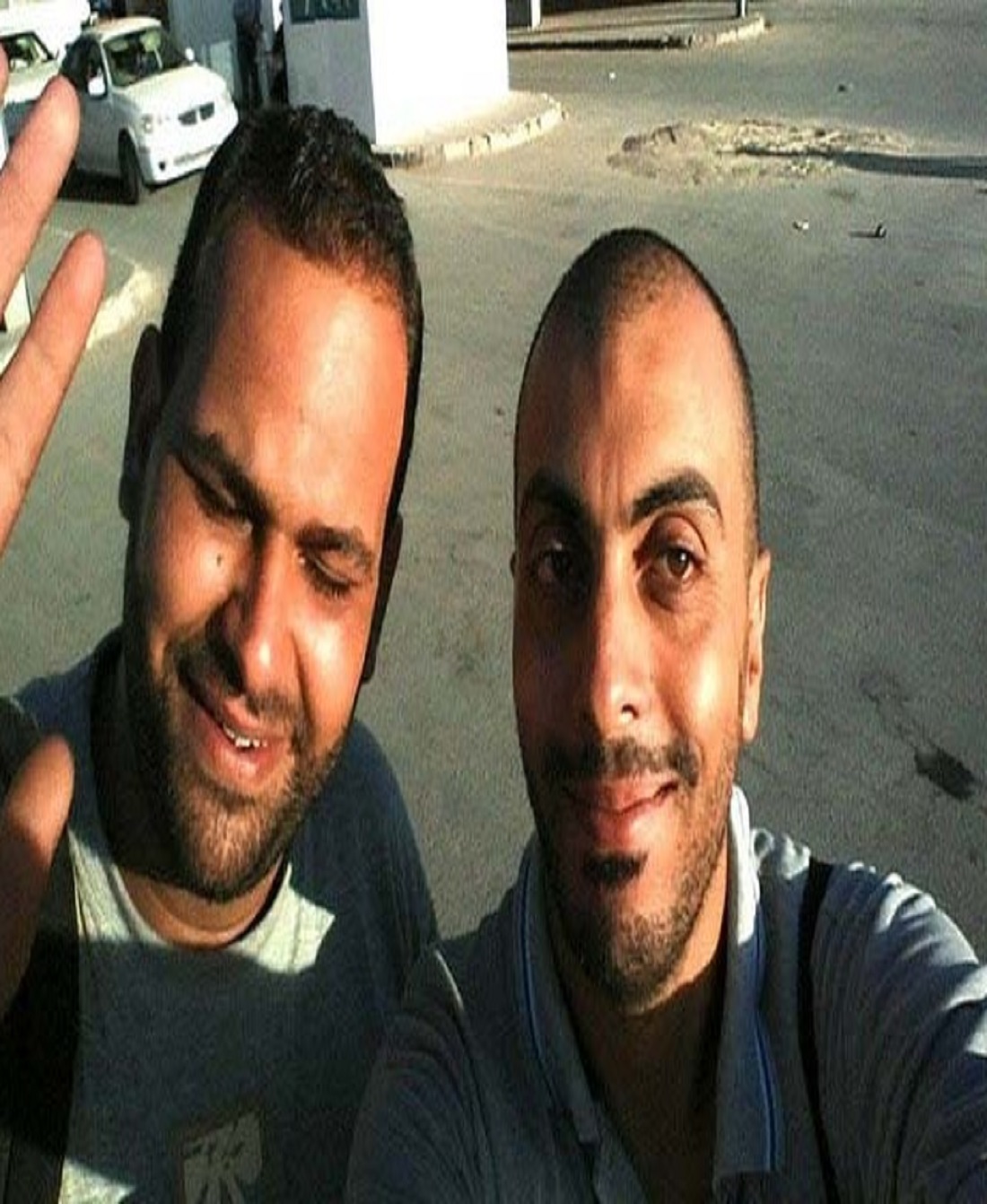

In September 2014, Tunisia was still living through the sweeping transformations brought by the 2011 revolution, and the Tunisian press at that time was striving to prove itself as a fourth estate capable of oversight and truth-seeking in a region engulfed by turmoil. Amid this climate, two young names stood out: Sofiane Chourabi, the journalist known for his bold writings and investigative articles, and Nadhir Ktari, the young photographer who had accompanied him on several assignments. Together, they embarked on a journalistic venture in Libya. Their choice was no coincidence; the neighboring country was going through one of the bloodiest and most turbulent moments in its modern history, with reports of militias expanding and the rise of the Islamic State in eastern Libyan cities dominating both Tunisian and international media. The two decided to cross the border on a professional mission in search of stories from the field, unaware that this journey would be their last, and that their disappearance would become a mystery lasting a full decade.

On September 3, 2014, while on their way to the city of Brega, they were intercepted by an armed group. They were forcibly taken to an unknown location, sparking fear within their journalistic circles. Yet after hours of tense anticipation, their release was announced. At the time, it seemed like an incident that could happen in any unstable environment. But fate had something heavier in store. Just five days later, on September 8, they vanished completely near Ajdabiya. Since that day, no one has seen Sofiane or Nadhir, marking the beginning of a family and national tragedy with no resolution.

In the first days following their disappearance, contradictory rumors spread: some claimed they were being held by a local group that would soon release them, while others suggested they had fallen into the hands of the Islamic State, which was beginning to impose control over eastern Libya. Media outlets circulated vague statements and posts on social media, alternately claiming that the two were safe or that they had been executed. In January 2015, a statement attributed to ISIS’s Libyan branch declared that the journalists had been killed. However, the announcement was not accompanied by photos, videos, or any material proof, which led many to doubt its credibility. The group had previously used graphic announcements as a propaganda tool and never hesitated to release images or videos when executing foreign hostages, which made the absence of evidence in Sofiane and Nadhir’s case raise more suspicion than confirmation of their deaths.

Then came April of that same year, adding yet another layer of ambiguity, when Libyan officials announced that detained individuals had confessed to killing the journalists and burying them in a remote area in the east of the country. International media reported these claims widely, but the absence of any physical evidence, forensic reports, or recovered bodies stripped the announcement of credibility and deepened suspicions. Was it simply a political attempt to close the file and ease international pressure? Or was a truth deliberately being concealed? No one had an answer.

In Tunisia, the impact of the news was devastating. The journalists’ families entered a cycle of grief and relentless searching. Nadhir Ktari’s mother quickly became a symbol of perseverance and determination. She traveled back and forth between Tunisia and Libya, met with both official and unofficial figures, spoke to local intermediaries, and tried to follow any lead, no matter how faint. It was not an easy journey; the areas where they were believed to have been held were under the control of warring armed groups, and movement between them was fraught with danger. Yet she refused to give up, and every time one lead evaporated, a new account would surface to keep hope alive.

The National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists also refused to remain silent. It organized demonstrations, issued statements, and raised the issue in international forums, arguing that the Tunisian state had not done enough to exert pressure and uncover the truth. International organizations such as Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists joined in, issuing strong statements demanding clarification of the journalists’ fate, warning that the ambiguity allowed impunity to prevail, and sending a dangerous message that journalists could be targeted without consequence.

But the problem was not a lack of intent, it was the complexity of the Libyan reality. In those years, eastern Libya was a battlefield of multiple forces: Khalifa Haftar’s troops on one side, local armed groups, the Islamic State, and militias with conflicting allegiances. This fragmentation made it nearly impossible to identify the party responsible for the kidnapping, let alone reach a secure location of detention. Politically, the division between the Tripoli and Tobruk governments only worsened matters, making official communication with Tunisia fragile and irregular, and stripping joint investigations of any real effectiveness.

In the autumn of 2014, the scene in Libya was boiling with unrest, while Tunisia’s eastern border held its breath, fearing that the flames of chaos might spill across. The country, drowning in armed conflict between two governments, two parliaments, and countless militias, was turning into ungoverned land where names could be erased, stories silenced, and human identities lost like scattered papers amid the rubble of destroyed cities. In that charged atmosphere, two Tunisian journalists, Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari, set out on a field assignment in Libya, searching for a story that could bring to Arab and international audiences a glimpse of the reality unfolding on the ground. They could not have imagined that their brief journey would turn into a long unresolved chapter lasting a decade, and that their names would become part of one of the most complex files in contemporary Tunisian journalism, one that exposed the fragility of regional relations and the weakness of protection mechanisms for journalists in conflict zones.

Sofiane Chourabi, a journalist known for his bold critical stance since the early post-revolution years in Tunisia, was a familiar face to the local public thanks to his strong television presence and his articles that never shied away from confronting political or religious taboos. With him on that trip was Nadhir Ktari, a young photographer who carried his camera as if it were an extension of his own eye, seeking light even in darkness, and capturing hope amid destruction. Both entered Libya with official authorization, under the umbrella of legitimate media cooperation. Yet their steps came to an abrupt halt near the city of Ajdabiya, where their trail disappeared under mysterious circumstances, opening a long saga of questions and waiting between contradictory statements issued by warring factions, evaporating diplomatic promises, and judicial investigations that remain endlessly open.

From the earliest hours of their disappearance, Tunisian and Arab media relayed conflicting reports. Some said the pair were being held by a local armed group that would soon release them. Others promoted the narrative that they had been executed by a terrorist organization that had extended its control over parts of Libya. Between these accounts, hope hung suspended, with no material evidence to confirm it, and no definitive denial to end it. The families of Chourabi and Ktari entered a harsh cycle of waiting, moving between government offices in Tunis, the headquarters of international human rights organizations, and waging an ongoing media battle to keep the case alive in public memory.

The first months were heavy with rumors: one day it was said they were executed in Sirte, another that they were in the hands of a hardline group linked to Ansar al-Sharia, then that they were moved to Derna or Benghazi, only for other reports to claim they were still alive, held by some party waiting for a deal or an exchange. The stories multiplied, but the fragile thread their families could cling to never materialized. Absence became solid reality, certainty dissolved like a dream, and only one great unanswered question remained: where are they?

The Tunisian state, from the beginning, lacked a clear strategy to deal with the case. The government was preoccupied with the challenges of democratic transition, parliament was mired in internal disputes, and the security apparatus was under heavy pressure from counterterrorism operations along the border. Nevertheless, repeated statements were issued affirming that efforts were ongoing in coordination with the Libyan authorities to uncover the journalists’ fate. Yet anyone following events knew that the phrase Libyan authorities was little more than an empty title, since Libya itself no longer had a unified authority. It was a country carved up among militias and rival political entities, each with its own areas of influence and rhetoric.

As the situation grew more complex, civil society organizations stepped in. The National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists organized solidarity actions, raised photographs of Chourabi and Ktari during protests, and issued repeated appeals to the international community to intervene. International human rights groups such as Reporters Without Borders and Amnesty International also adopted the case, reminding the world that protecting journalists in conflict zones is a collective responsibility, and that governmental silence verges on complicity. Even so, the file remained stagnant, as though it had simply joined the long list of unresolved cases of enforced disappearance destined to linger indefinitely.

The hardest part of this case was not only the uncertainty shrouding the journalists’ fate, but also the glaring contradictions in official Libyan statements. On several occasions, authorities claimed to have arrested the perpetrators of the kidnapping, or to have obtained confessions confirming their execution, only for it to become clear that no material evidence supported such claims. At one point, a government aligned with Tobruk announced that the journalists had been killed and buried in an unknown location, only for other bodies later to deny it and assert they were still alive. These contradictions compounded the tragedy, mixing hope with despair, and placing a cruel psychological burden on their families, trapped between expectation and disappointment.

As the years passed, the case became a mirror of the state of Tunisian media after the revolution. Freedom of expression, such a great achievement, suddenly found itself facing a harsh test. Could a journalist do his work in conflict zones without putting his life at risk? And if he did fall victim to a wider geopolitical game, could the state protect him or bring him back? The case of Chourabi and Ktari answered bitterly. In the Arab world, journalists remain vulnerable to militia bullets and government silence, and their stories can be erased unless civil society clings to them and turns them into symbols that refuse to fade.

But the case did not end, nor could silence bury it. Every year, the National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists organized demonstrations on the anniversary of their disappearance, raised their portraits in the heart of the capital, and reminded everyone that the wound remained open, that delayed justice may linger but does not die. With each of these commemorations, the names Sofiane and Nadhir became part of Tunisians’ collective memory, symbols of the price of freedom.

At the beginning of 2015, the uncertainty surrounding the fate of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari became even more entrenched, as the search for truth turned into a long journey of painful waiting, marked by fleeting glimpses of hope and repeated disappointments. That year, media reports increasingly highlighted the rise of extremist groups in eastern Libya and the growing cases of kidnappings and summary executions, making any local or international investigation fraught with danger. No single authority could confirm or deny any information with certainty, placing Tunisia before an unprecedented challenge: how to protect journalists who had disappeared outside its borders while the ruling power in the host country was either absent or deeply divided.

The families of the journalists did not stand idle. Nadhir’s mother, with unyielding determination, traveled to Tripoli, Benghazi, and Ajdabiya, meeting with local officials, mediators, and even members of local militias in an effort to follow any lead that might point to her son’s whereabouts. During these visits, she faced both security and political obstacles: the roads were dangerous, and the prevailing chaos made every piece of information questionable and every government promise practically meaningless on the ground. Still, she persisted in collecting testimonies, documenting what she could, and building a small database that might one day help retrace the path of her son’s disappearance.

At the same time, the Tunisian authorities attempted to coordinate with Libya’s interim government and with United Nations missions in the country to exchange information. Yet internal divisions and practical constraints made these efforts limited in effect. Libya was divided between the governments of Tripoli and Tobruk, each controlling different parts of the east, while local militias acted according to their own interests. This made it extremely difficult to identify the kidnappers or pinpoint the exact location of detention.

Furthermore, several contradictory statements were issued by different Libyan parties during those years. Some claimed the journalists had been killed, while others hinted at the possibility that they were still alive. In 2016, a Libyan newspaper published claims from a former security official who said he had obtained confessions suggesting that the journalists were alive in an undisclosed location. Yet this information was never backed by concrete evidence and remained a solitary testimony added to the pile of uncertainty.

Meanwhile, the case became a symbol of the dangers of journalism in conflict zones. International media organizations began warning that any journalist covering conflicts in Libya without sufficient protection was at risk of abduction or death. Campaigns were launched to remind governments of the need for serious protection mechanisms, including rescue teams, strong diplomatic coordination, and clear procedures for dealing with kidnappings. While these movements gave the case a broader international dimension, they never translated into tangible solutions on the ground. The two journalists remained missing without a trace.

In the years that followed, reports continued about the movements of the Chourabi and Ktari families and their relentless efforts to pressure the Tunisian government to pursue their sons’ case with greater seriousness. Additional testimonies emerged from Libyans who claimed to have seen the journalists held by local militias, but these accounts were often delayed and unverifiable, adding yet another layer of complexity and uncertainty.

Between 2017 and 2018, with the decline of the so-called Islamic State’s influence in eastern Libya, new opportunities for investigation appeared. Still, the security and political challenges persisted. The region never truly stabilized, and the continuing dominance of local militias imposed a kind of de facto control over movement and mobility. This reality weakened any official attempt to determine the journalists’ whereabouts or their final fate, prolonging the agonizing wait for their families and for Tunisian and Arab public opinion.

The case also became a focal point in broader debates about press freedom and journalist safety in the Arab world, particularly for those covering wars and armed conflicts. The names of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari became examples of how fragile journalist protection can be, of the cost of truth in environments ruled by violence, and of the extreme difficulty of balancing professional duty with real danger. The Tunisian press, which had gained its freedom after the revolution, suddenly faced a harsh test: could it protect its own, could it pressure governments, or leverage international organizations, to reveal the fate of its citizens who disappeared in a neighboring unstable country?

To this day, the families hold on to faint hope, despite the passing years. Each year, symbolic demonstrations, raised portraits of the journalists, and reminders to the authorities remain part of an ongoing effort to keep the case alive and prevent it from fading into the flood of daily political news. And since no bodies have been recovered and no final material evidence presented, the long absence has become a symbol: of free journalism, of the human ordeal in the face of injustice and chaos, and of the eternal struggle between truth and ignorance, between hope and despair.

As the second decade after the disappearance of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari begins, questions have only grown about Tunisia’s ability to protect its journalists abroad, and about the failure of local authorities in Libya to provide any guarantees of safety. What began as an individual tragedy gradually turned into a symbol of journalism under threat in conflict zones. From 2019 to 2024, Tunisian and Arab media closely followed the movements of the journalists’ families, officials’ statements, the republishing of older reports, and expert analyses, keeping the case alive in public consciousness even after more than a decade had passed since their disappearance.

In this context, the role of international organizations became increasingly prominent. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued annual reports reminding the world that the Tunisian journalists had not been forgotten, stressing that their disappearance represented a grave violation of human rights and press freedom, and calling on Arab and international governments to pressure Libyan authorities to uncover their fate. Reporters Without Borders also included the case in its reports on the dangers faced by journalists in conflict zones, emphasizing that it represented a dangerous precedent for impunity and highlighted the fragility of legal and diplomatic support available to journalists working abroad.

The human side of the case remained the most poignant. The families, especially Nadhir’s mother, never ceased searching, lobbying, and demanding the right to know what happened to their sons. In scattered interviews with Tunisian and Arab media, she spoke of her journeys to Libya, of meetings with Libyan officials, of countless closed doors and unanswered questions, and of the psychological pain that accompanied every anniversary of the disappearance. That pain became a symbol of the suffering endured by journalists and their families, and of the true human cost of seeking truth in chaotic environments.

Regional politics played a central role in prolonging the mystery. Libya remained deeply unstable, torn between rival governments and dominated by militias exercising power over specific territories. This reality made any independent investigation nearly impossible. Tunisia, for its part, attempted diplomatic pressure, but faced practical limitations. Libyan authorities were unable to guarantee Tunisian security teams access to precise locations, and most information continued to depend on local intermediaries and unverifiable testimonies.

Over time, efforts emerged to turn the case into a platform for public awareness about press freedom. Awareness campaigns, university lectures, conferences on the risks of conflict reporting, and media features used the story of the two young journalists as an example of the dangers of the profession. Digital platforms and social media amplified their images and stories, sparking debate about the state’s role in protecting journalists and about the importance of stronger international mechanisms to address abductions and enforced disappearances.

Legally, the challenges persisted. Official positions often contradicted human rights reports, and sporadic confessions allegedly obtained by Libyan authorities under pressure or through mediation could not be regarded as conclusive evidence of the journalists’ fate. The absence of physical proof, the failure to produce bodies, and the lack of comprehensive investigative reports left the case suspended in a legal and diplomatic vacuum, adding yet another layer of complexity to the families’ ordeal.

The case’s media impact extended beyond Tunisia to the Arab world. The names of Sofiane and Nadhir became part of a broader conversation on the targeting of journalists in conflict zones, and on the responsibility of governments and international organizations to protect freedom of the press, especially in environments where law is absent or exploited for political ends. At the same time, human rights advocates demanded that the international community shoulder its responsibilities, arguing that the absence of truth exposed the failure of global mechanisms to stand by journalists and their families.

On a personal and human level, the pursuit of truth became a saga of patience and perseverance. Nadhir’s family, which continued to push relentlessly through media, legal, and diplomatic channels, became an example of resilience in the face of absent justice. Sofiane’s family, meanwhile, followed every lead through the media and participated in every initiative that might reveal their son’s fate. As time passed, this human effort itself became a symbol of the families’ endurance and a voice insisting on the right to know, no matter how long the wait or how dim hope sometimes seemed.

In recent years, as security and political dynamics in Libya shifted, new opportunities for investigation occasionally emerged. Yet the recurring patterns of insecurity, political division, and weak central authority repeatedly recreated the same obstacles. Despite this, efforts never ceased. Tunisian media continued to highlight the case, keeping it firmly on the national and human rights agenda. By then, the matter had transcended the disappearance of two individuals to become a symbol of the need to protect journalists, and of the importance of truth and transparency in the face of chaos and uncertainty.

Today, more than a decade after the disappearance of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari, their case stands as a stark reminder of journalism under attack, of the difficulty of protecting individuals in conflict zones, and of the urgent need for both local and international communities to develop effective mechanisms for addressing enforced disappearances. The long absence has not silenced advocacy, nor erased the story from public memory. On the contrary, the two journalists’ names have become part of a collective consciousness and an emblem of perseverance in pursuit of truth. While their ultimate fate remains unknown, the quest to uncover it endures as both an ethical and human duty, and as a silent message to all who encounter their story about the true cost of professional courage, and the responsibility of states and societies to safeguard journalists under all circumstances.

With more than a decade having passed since the disappearance of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari, it has become necessary to view the case not only from a Tunisian perspective but within the broader regional context that encompasses Libya’s political upheavals, international interventions, and the impact of security chaos on press freedom across the Arab world. Since 2011, Libya has known no real political or security stability. It became fertile ground for the rise of scattered militias, local and regional armed conflicts, and deep political divisions between two rival governments, each controlling specific territories and imposing its authority on local populations. In such an environment, journalists could only move with extreme caution, as abduction or armed violence had become not an occasional threat but a daily reality.

The case also highlights the fragility of legal systems in addressing enforced disappearances, especially when they occur in countries with limited sovereignty or fractured institutions. Tunisia attempted diplomatic communication with Libyan authorities, but the absence of a strong central authority and the dominance of militias with shifting loyalties rendered these efforts insufficient. This reality made the disappearance of Chourabi and Ktari more than a personal tragedy. It became a mirror reflecting the region’s inability to protect journalists in conflict zones, and a symbol of the risks born out of the intersection of politics, security, and media freedom.

On the human level, the families’ endurance turned into a profound experience of perseverance and sacrifice. Every meeting with an official, every visit to a location rumored to hold the journalists, every message shared through the media, was an attempt to keep hope alive and to assert that the absence of truth did not mean acceptance of tragedy. Nadhir’s mother, who became a media symbol of determination and a persistent voice for justice, embodied human resilience in the face of losing a son without proof of his fate. This human suffering, compounded by the absence of justice, created a narrative stronger than any official statement: a story about the value of life, the duty of society to protect its members, and the true cost of seeking truth.

The case also demonstrated the influence of digital media and social networks in keeping stories alive even amid governmental silence or institutional weakness. Images of the journalists circulated widely, their story retold, and campaigns were launched each year to mark their disappearance. These efforts preserved public awareness of the case in Tunisia and across the Arab world. They were not mere symbolic gestures but a tool of constant pressure, a reminder that journalism does not forget those who vanished while fulfilling their professional duty.

At the international level, human rights organizations stressed that the lack of physical evidence should not overshadow the essential truth: the two journalists disappeared while on assignment, and the absence of serious or independent investigations revealed structural failures in protecting journalism. Some groups linked their case to the disappearances of other journalists in conflict zones worldwide, turning it into a tragic model discussed at press freedom conferences and journalist safety forums. It became evidence of the urgent need for more effective protection mechanisms and consistent diplomatic support in cases of abduction or disappearance.

Regional politics played a central role in prolonging the uncertainty. Libya remained a land of disorder, dominated by militias across large swaths of territory, which prevented any independent investigation from accessing precise sites. Tunisia, despite multiple attempts to obtain reliable information, was constrained by political and diplomatic entanglements and by a reluctance to risk military or security involvement. As a result, files remained open without clear answers.

In recent years, as some armed groups in Libya weakened, new opportunities arose for closer investigations. Yet ambiguity persisted. Doubts continued about whether the journalists were still alive or had been killed, and whether certain parties sought to close the case for political or security reasons. Here, the political reality intersected with the human dimension: every old or new piece of information became a thread to follow, while every attempt to find tangible evidence remained fraught with risk.

Ultimately, more than ten years on, the case of Sofiane Chourabi and Nadhir Ktari remains open to every possibility. Yet it has transcended the personal to become an emblem of free journalism, a reference point in studying the pursuit of truth in conflict zones, and proof of the fragile state of journalist protection across the Arab world. The long absence did not silence advocacy. On the contrary, it reignited focus on the urgent need to build genuine protective mechanisms, to strengthen civil society, and to uphold the value of professional life for those who choose to confront reality under the harshest conditions.

Today, the case lives on in collective memory, carrying many messages: about journalistic courage, about the price of truth, about the moral and legal responsibility of both state and society, and about the power of media in revealing what might otherwise remain hidden. While the mystery endures, the search for truth has become an ethical obligation and a silent message to anyone who encounters the story about the true cost of professional bravery, about human resilience in the face of injustice and chaos, and about the enduring struggle between hope and despair, between truth and ignorance.