Irfan Magazine: The Magazine for Children Everywhere

From the moment that Abdelhamid El Ksentini and his colleagues conceived the idea of Irfan magazine, they embarked on a venture that combined education, culture, and the joyous spirit of childhood in a newly independent Tunisia. The group behind the magazine included educators, youth leaders and writers associated with the Tunisian Union of Youth Organizations. They shared a conviction that children needed a publication grounded in Tunisian identity yet open to wonder, discovery and imagination. El Ksentini himself had a background in youth education and journalism. He believed that childhood deserved respect and that magazines for children could offer more than simple amusement. They could build linguistic, moral and civic awareness from an early age.

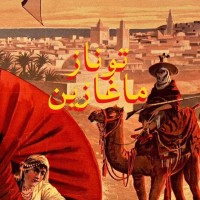

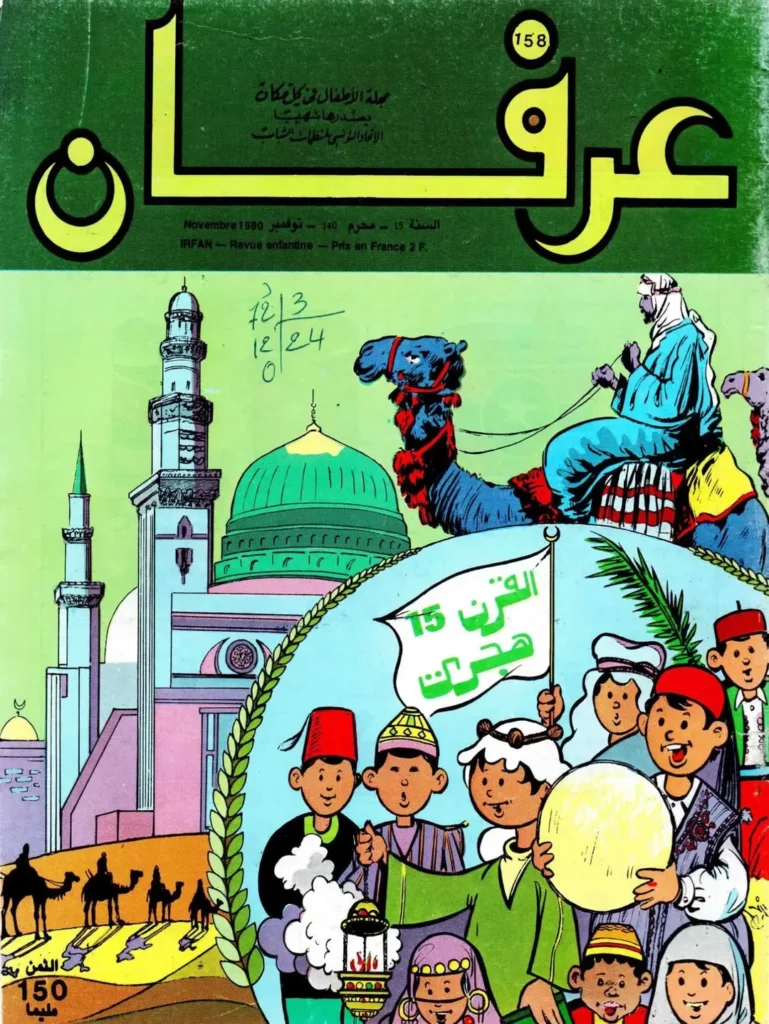

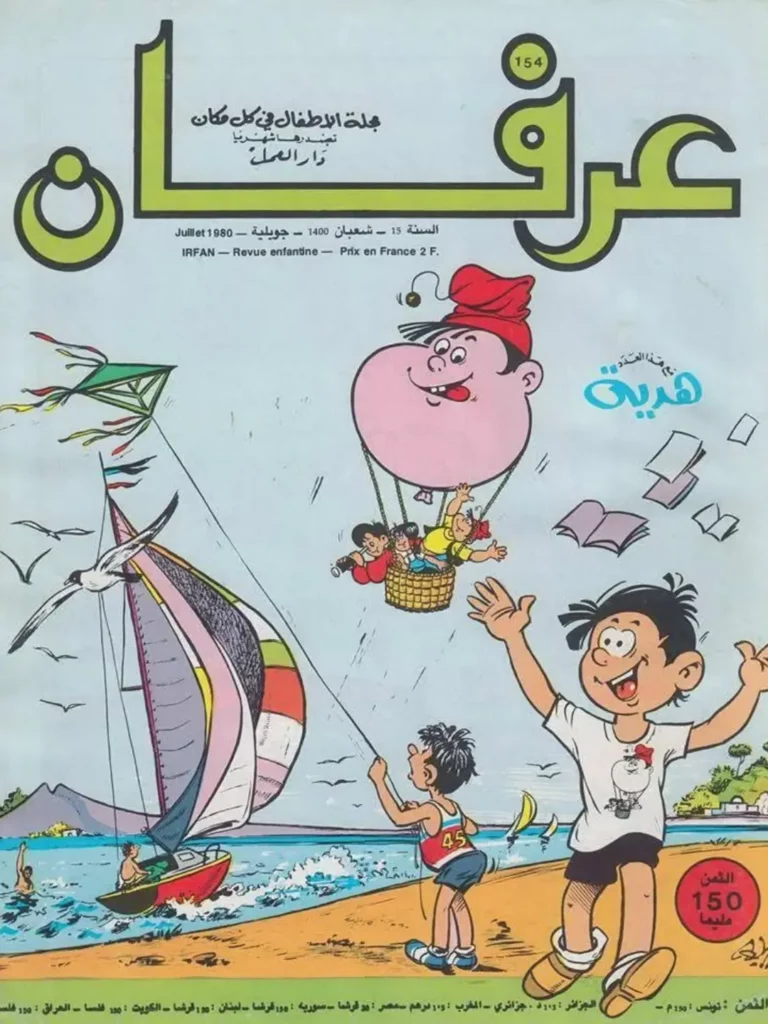

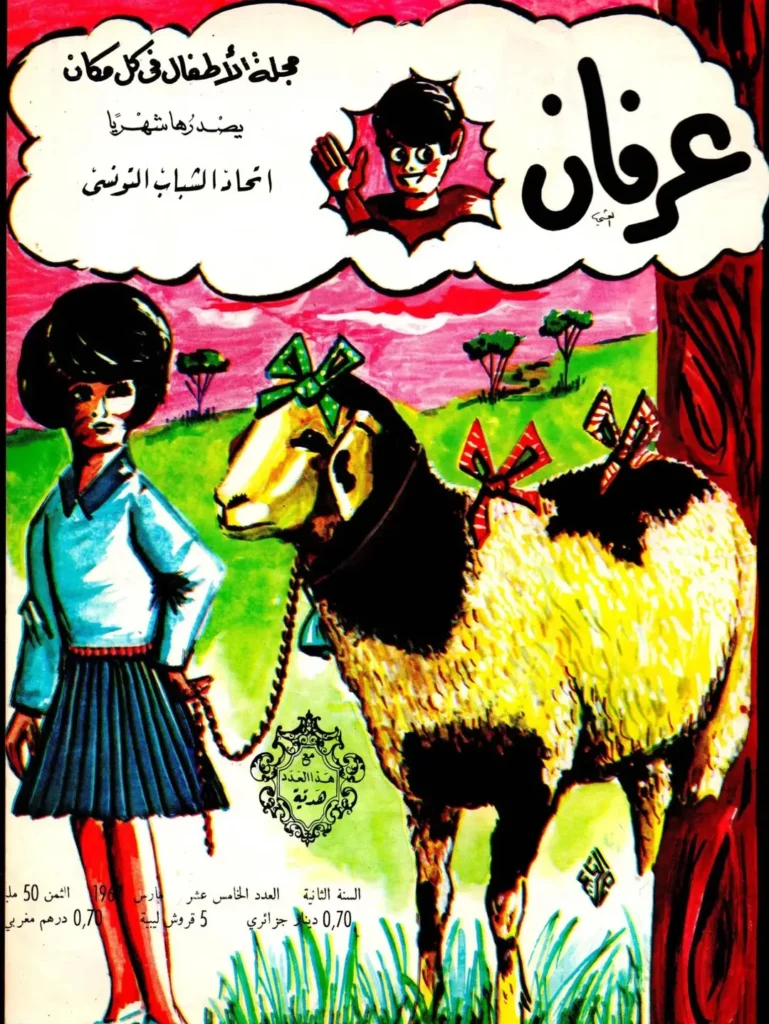

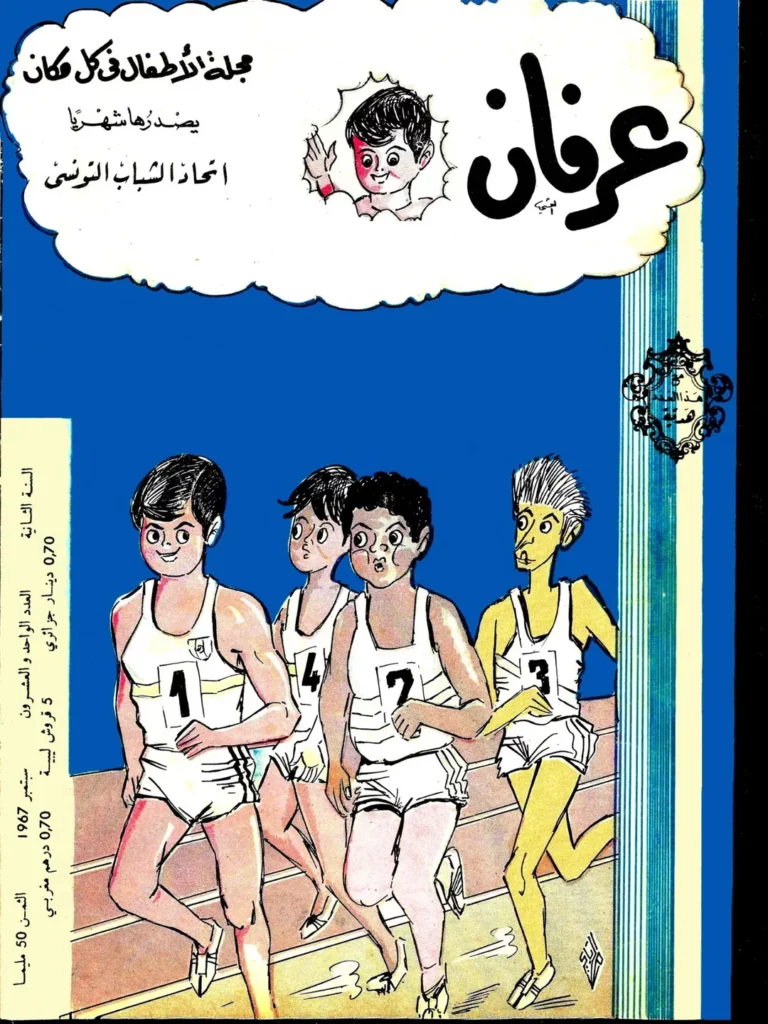

The launch of Irfan in 1966 was therefore a carefully orchestrated act. The Tunisian Union of Youth Organizations provided institutional backing and initial funding. The name Irfan was chosen to evoke knowledge and recognition. Its slogan was “magazine for children everywhere.” The editorial model was ambitious. The magazine was printed by Dar Al Amal which specialized in quality colour printing. That choice allowed Irfan to appear as a vibrant, attractive, high quality product. Each issue comprised roughly thirty six pages. Eleven or so pages were devoted to comic strips and illustrations. The team included writers who authored short stories and poems. They also commissioned educators to write simple scientific explanations. Contributors created puzzles and riddles. They included short dramatic plays that could be performed at school. They assembled moral stories rooted in Tunisian life. The result was a carefully curated mix of content that nurtured imagination, intellect and identity.

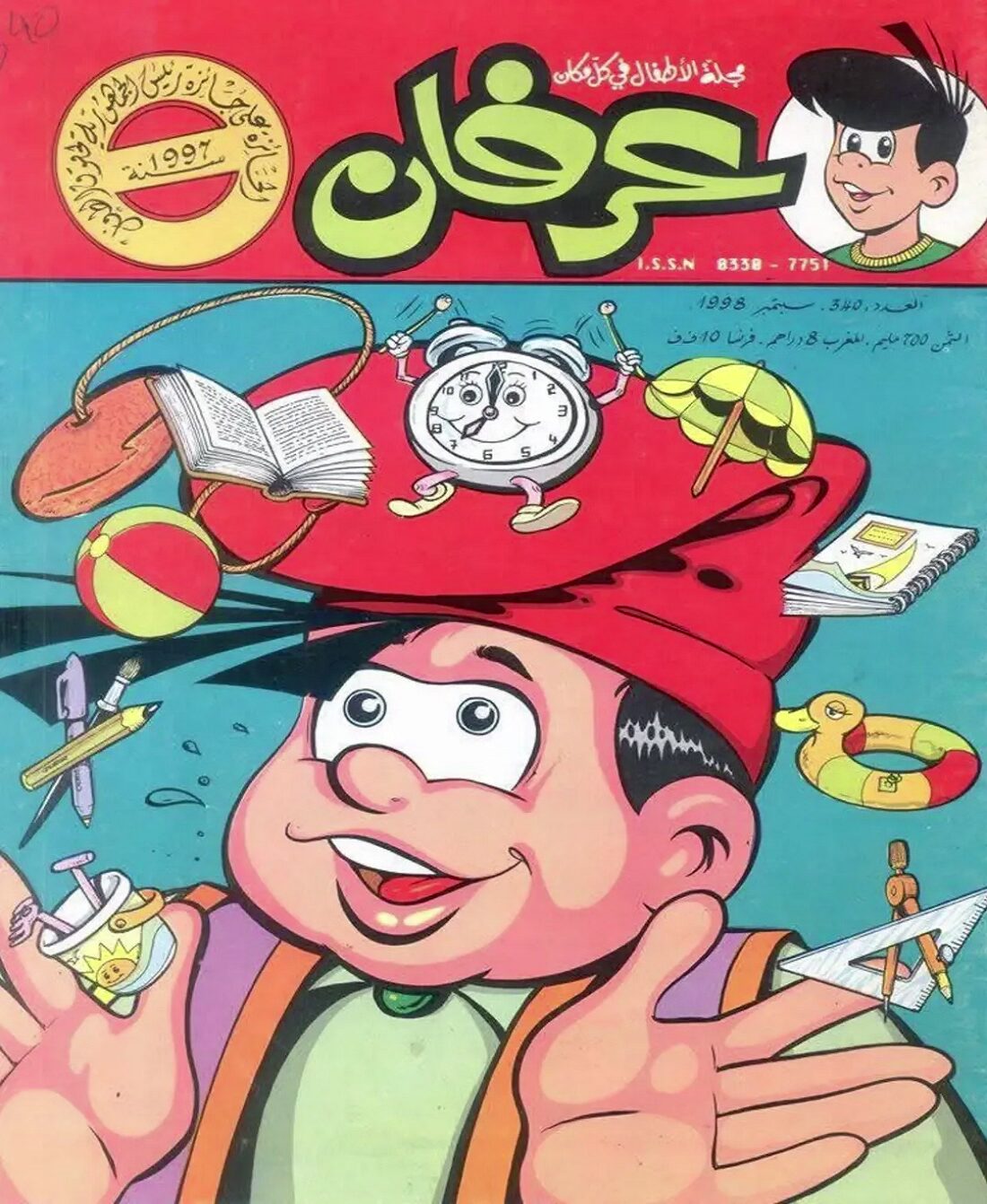

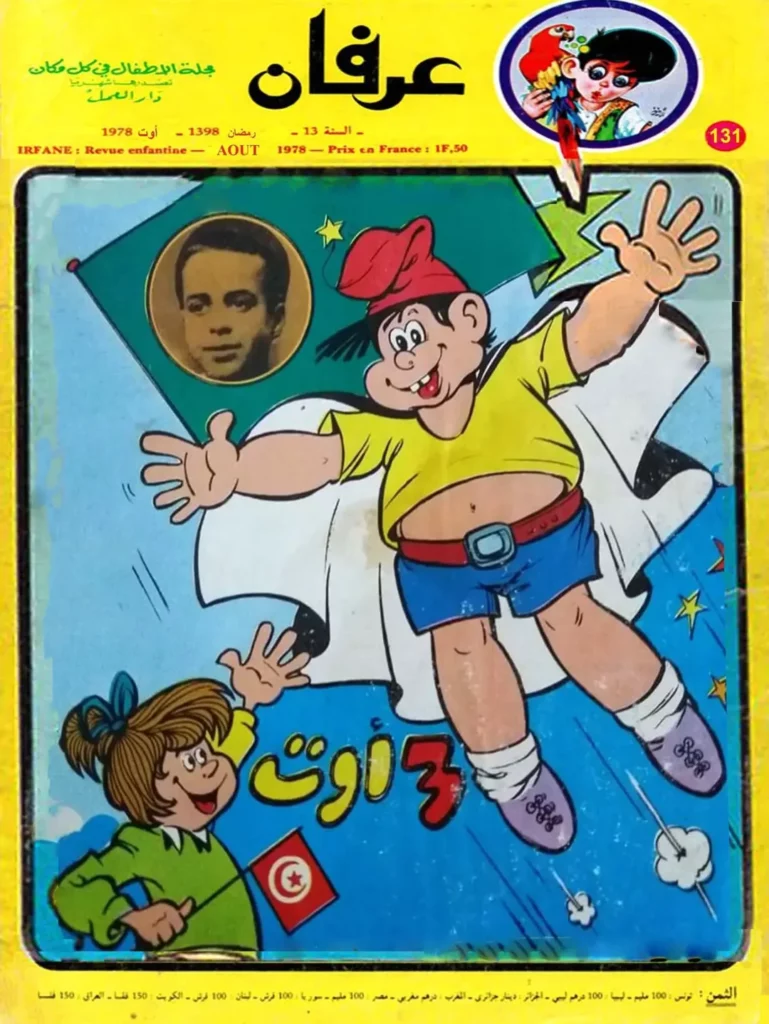

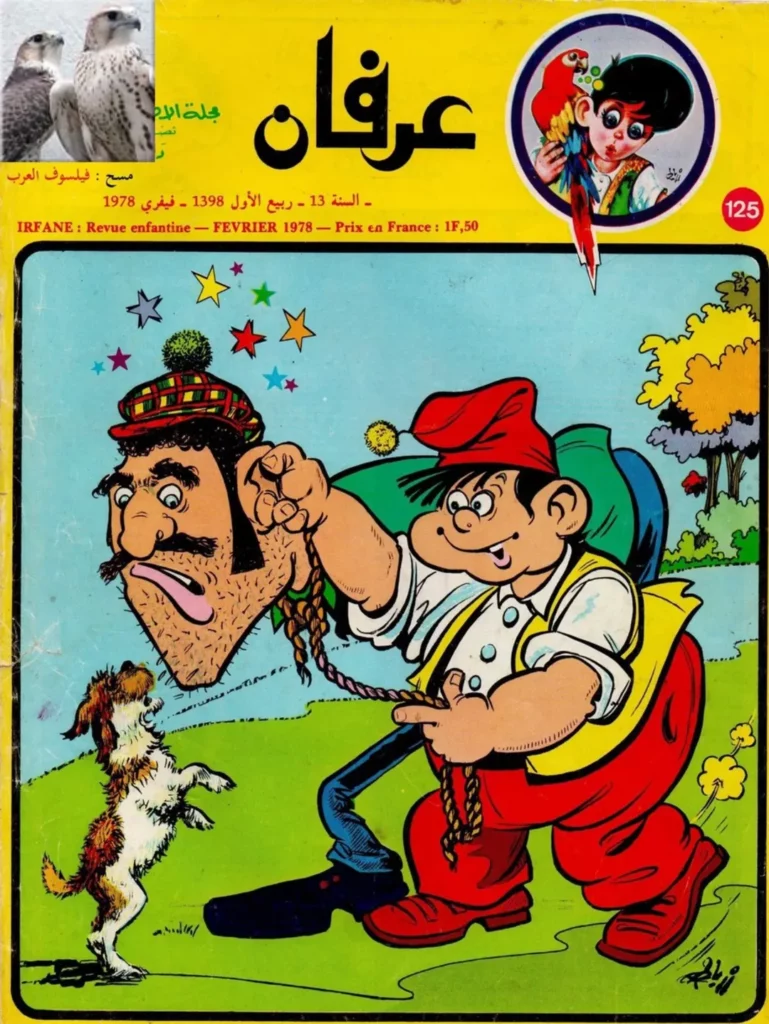

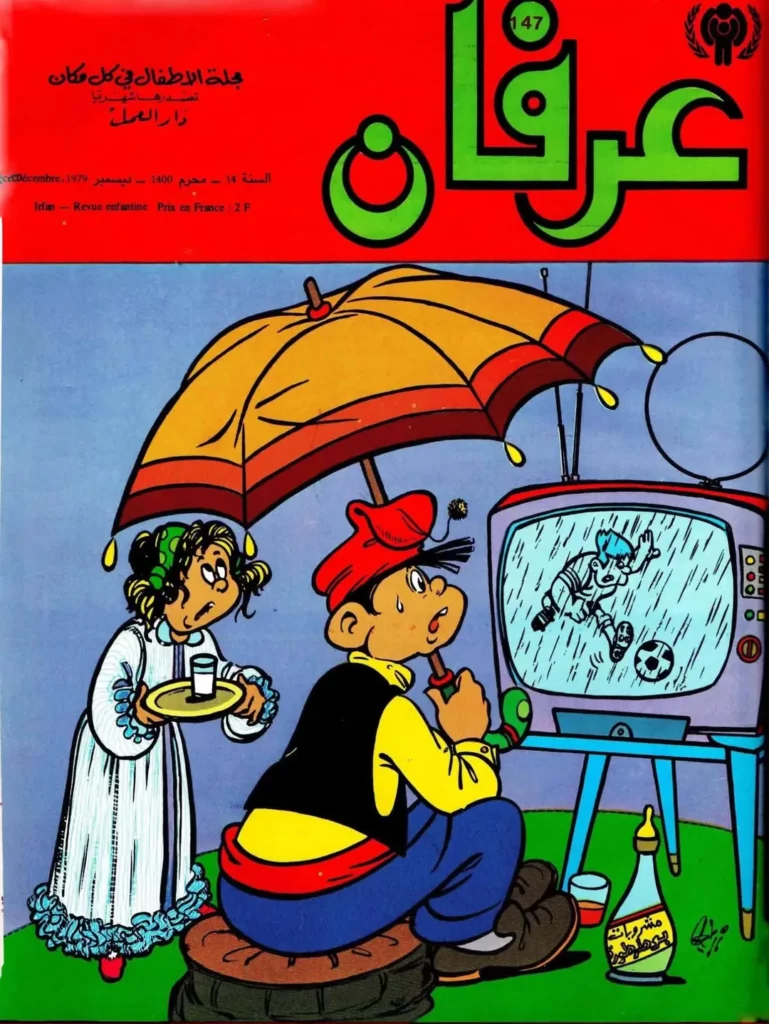

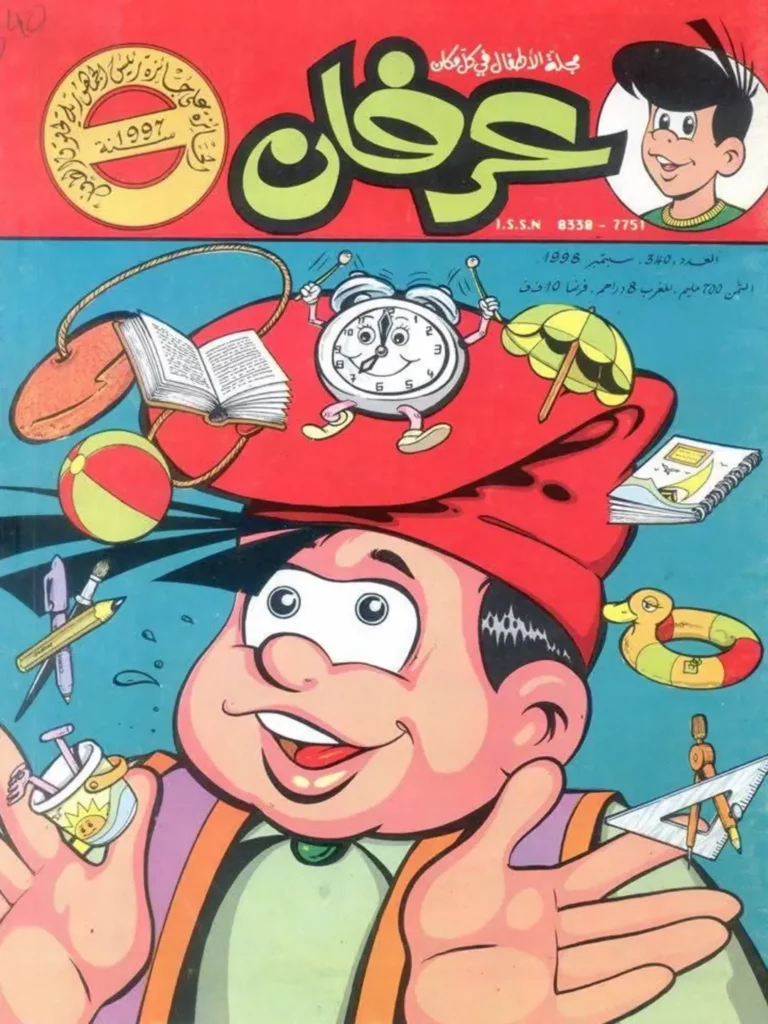

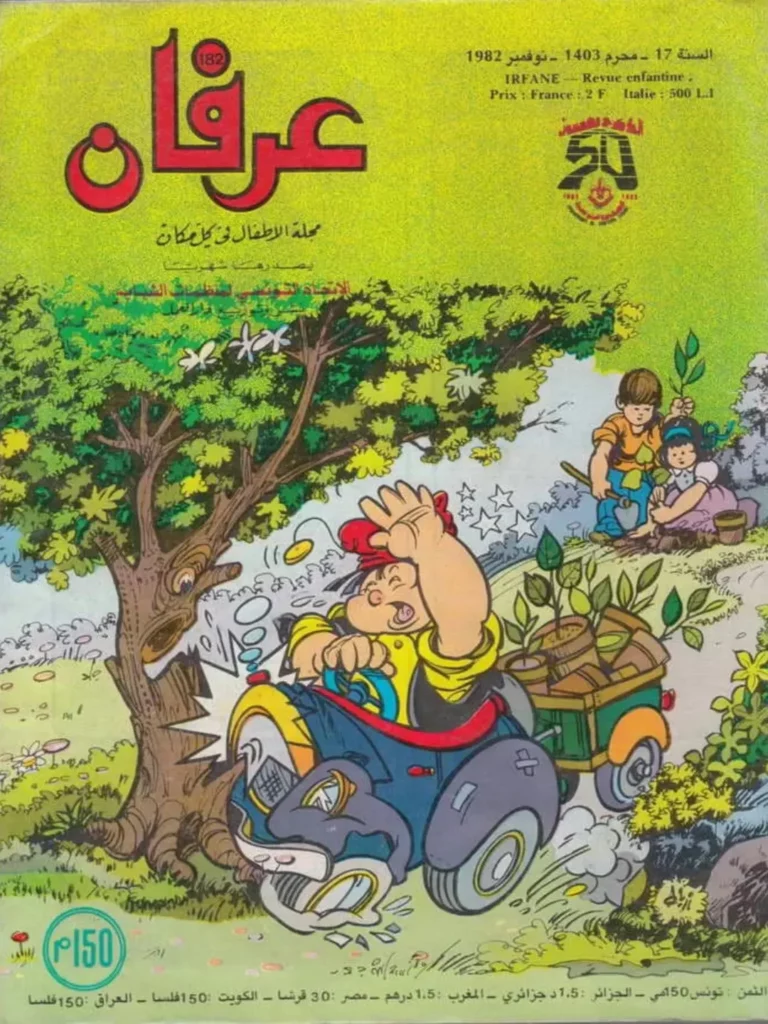

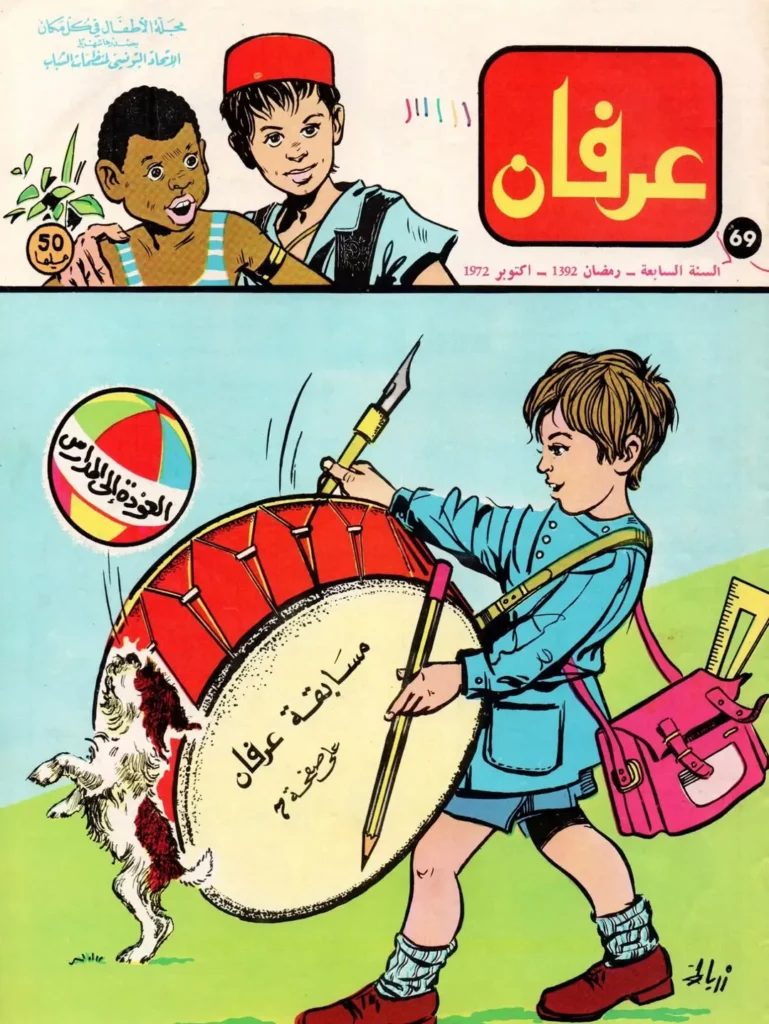

Boutartoura became the mascot of Irfan. This character, with a round belly and a red hat, appeared repeatedly on the cover. Children awaited his appearance with excitement. He embodied the friendly and whimsical tone of the magazine. The decision to feature such a mascot reflected an understanding of how branding could create emotional attachment in a young readership.

In the 1970s Irfan continued to benefit from stable institutional support. The Union of Youth Organizations maintained a team of editors and illustrators. Circulation was regional but significant. The magazine reached schools, youth clubs and homes across the country. Readers wrote letters and submitted drawings. Editorial letters began to publish responses from children. That interaction strengthened the magazine’s role as a cultural community for young readers.

Yet during this period Tunisia began to confront economic challenges. The late 1970s saw austerity measures. The budget allocated to cultural initiatives became unpredictable. Irfan began to feel the strain. Some issues were delayed. Page counts fluctuated. Colours became less vivid. Staffing became irregular. By the early 1980s pressure on funding increased further. The editorial team worked with fewer resources. Occasional gaps appeared in publication. Yet many readers stayed loyal. They recalled each issue as a small window into curiosity and delight.

The arrival of mass media created new competition. Television programs aimed at children appeared. Imported comic books and illustrated magazines gained popularity. Children were exposed to foreign images and narratives. Irfan responded by reinforcing its content rooted in Tunisian experience. Science sections explained local geography and folklore. Stories included traditional tales retold with modern sensibility. These efforts slowed decline but could not reverse it entirely.

In the 1990s the magazine entered a period of decline. Printing costs increased. Paper shortages occurred from time to time. Distribution channels frayed. Circulation dropped. The editorial team had fewer contributors. Some issues became special editions rather than regular monthly publications. Schools and libraries began stocking fewer copies. Nevertheless a core of readers and former contributors remained invested in its continuation. They remembered the magazine as formative. They passed on memories to children and grandchildren. Some preserved copies. A few began collecting and archiving the old issues with personal affection.

In the early years of the 2000s Irfan appeared to have vanished. Only sporadic special issues were released, perhaps to commemorate anniversaries. The Union of Youth Organizations was preoccupied with other priorities. The magazine’s infrastructure had largely dissolved. Yet cultural actors, educators, researchers and former editors continued to speak of its value. They recognized it as a reference in Tunisian childhood culture. Its absence created a noticeable void. People spoke of its disappearance in articles and online posts. They showcased images of old covers. They lamented the loss of tactile reading experiences, of evocative art and stories that spoke directly to Tunisian children.

When Abdelhamid El Ksentini died in January 2019 the community felt a collective grief. He had been an enduring voice for children’s journalism. He had advocated for the magazine and for the principle that children deserved media that respected their minds. His death sparked widespread reflections on the fragile legacy of Irfan. Many lamented that he would not be there to witness any revival. His absence brought renewed attention to the magazine’s significance in cultural memory.

Then in March 2019 Irfan was relaunched. A private patron funded the initiative. He was a Tunisian businessman and cultural philanthropist who valued tangible cultural heritage. The magazine appeared with a modern layout, yet the editorial team consciously preserved the tone and values of the original. Many former readers volunteered or contributed. Educators and writers involved in early decades returned. Illustrators revived familiar styles. New writers and artists joined the project. The relaunched magazine featured a combination of nostalgia and innovation. Covers recalled traditional designs. Inside the content ranged from stories addressing contemporary issues to reflective pieces examining media, reading and identity. Letters pages welcomed children’s voices again. Schools began subscribing once more.

The reception was warm and emotionally charged. Former readers expressed joy at holding a new issue, at seeing the revived mascot, at rereading poems and plays that echoed their youth. Scholars framed the return of Irfan as cultural resilience. They argued that in an era dominated by digital platforms, there was enduring value in printed childhood media. They talked about how Irfan became a site of intergenerational connection. Grandparents and parents who knew the original shared reading time with children creating moments of continuity across time.

Today Irfan is a case study in cultural continuity and media adaptation. It offers reflections about the role of children’s publications in national identity, in the balance between state supported and privately sustained cultural projects, and in the sensory importance of printed text and image. It raises questions about how societies value imagination, nostalgia and durable formats in childhood media. Irfan has shaped not only individual memories but a sense of collective belonging. Preserving it requires more than nostalgia. It requires sustainable funding models, creative editorial leadership, robust distribution, institutional recognition and educational partnerships. From founding in 1966 to decline and revival in 2019 its story maps the changing landscapes of Tunisian cultural life. It invites us to consider whether childhood culture can be both a heritage to remember and a living practice to sustain.