Did The Beatles Ever Come to Tunisia?

Yes, they came, but not like this, and perhaps not all of them.

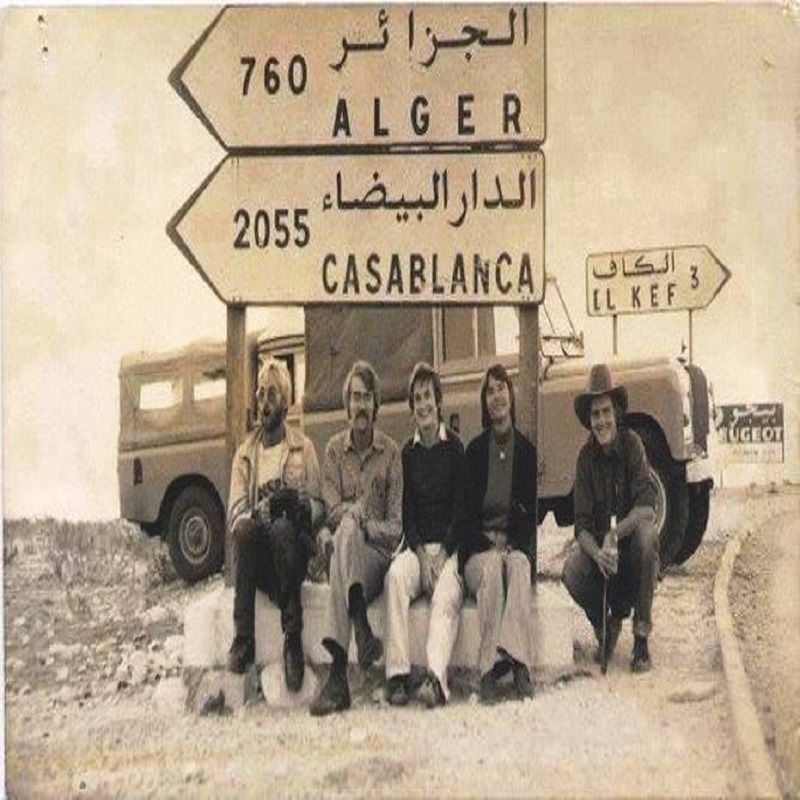

For years, a photograph has circulated widely on the internet, particularly from the late 2010s onward, claiming to show The Beatles somewhere in Tunisia. Often accompanied by captions pointing to road signs for Algiers, Casablanca, or El Kef, the image gradually entered the realm of online folklore. It appeared on Facebook pages, nostalgic forums, and regional social media groups, usually without context, but always with certainty. Yet despite its persistent circulation, the photograph does not depict The Beatles, and there is no verified historical evidence that the four members ever visited Tunisia together.

This confusion is understandable. The Beatles are among the most mythologized figures of modern culture. Their movements, appearances, and private moments have been relentlessly documented, recycled, and romanticized. When an evocative vintage photograph surfaces, especially one situated in a geography rarely associated with them, the desire to believe becomes stronger than the need to verify. The story feels exciting, forgotten, almost secret. But historical feeling is not historical fact.

What is often cited instead is a quieter narrative that Paul McCartney alone traveled to Tunisia in February 1965, accompanied by his then partner Jane Asher. This account appears across biographies, fan archives, and music history websites, frequently repeated but rarely anchored in primary documentation such as travel records, contemporary press coverage, or official correspondence. According to these secondary sources, McCartney sought temporary distance from the overwhelming intensity of Beatlemania, and Tunisia, specifically Hammamet, was chosen for its discretion and calm.

If the visit did occur, it was neither a concert nor an official appearance. It was described as a retreat. Accounts suggest the couple stayed in a secluded villa reportedly linked to diplomatic circles, walked along the coast, and avoided public attention. During this stay, McCartney is said to have begun working on the song Another Girl, later recorded for the album Help shortly after his return to England. This association, frequently cited online, gives Tunisia a modest place in Beatles history, not as a stage, but as a possible site of creative withdrawal. Still, it must be emphasized that this connection remains circumstantial, built on repetition rather than definitive evidence.

The viral photograph, by contrast, operates differently. Its power lies in ambiguity. The figures resemble musicians, the setting feels cinematic, and the road signs evoke youth, movement, and escape. Once labeled The Beatles in Tunisia, the image no longer required proof. Repetition replaced verification, and circulation became validation. This is how contemporary myths are produced, not through invention, but through unexamined accumulation.

Social media accelerated this process. Each repost stripped away hesitation and reinforced belief. Over time, familiarity substituted for truth. Only later did users begin to question the claim, pointing out discrepancies in facial features, chronology, and the complete absence of corroborating historical records. No known itinerary, photograph, or eyewitness account supports the idea of a collective Beatles visit to Tunisia.

The more plausible story, if it is true at all, is far less spectacular. Paul McCartney did not arrive as an icon seeking attention, but possibly as a young man searching for quiet. If Tunisia played any role in Beatles history, it did so discreetly, almost invisibly. Such moments, undocumented and fragile, resist certainty. Yet they are more human than any viral fantasy.

The Beatles did not visit Tunisia together. The circulating photograph is not of them. And even Paul McCartney’s presence remains based on indirect sources rather than confirmed archival proof. But perhaps this uncertainty is precisely the point. History does not always announce itself clearly. Sometimes it survives only as a trace, a rumor, or a cautious possibility, and sometimes that restraint matters more than spectacle.