Ten Years of As I Open My Eyes

Ten years after its first screenings, As I Open My Eyes remains a rare film that has not aged into nostalgia. Instead, it has settled into history with a quiet clarity, retaining its power precisely because it never tried to announce itself as a statement or a prophecy. Directed by Leyla Bouzid and released in 2015, the film now stands as one of the most lucid cinematic documents of Tunisia on the eve of rupture, observed not through slogans or spectacle, but through everyday gestures, sounds, and silences.

Set in Tunis during the summer of 2010, the film unfolds in a period that was, at the time, unnamed. Bouzid situates her story just before the fall of the Ben Ali regime, yet she avoids retrospective emphasis. There is no explicit anticipation of revolution, no foreshadowing framed for historical comfort. What the film captures instead is a state of suspension. Life continues under constraint, routines persist, ambitions exist but remain provisional. The future is present only as tension. This temporal restraint is central to why the film continues to resonate a decade later. It does not explain history. It preserves a moment before history intervened.

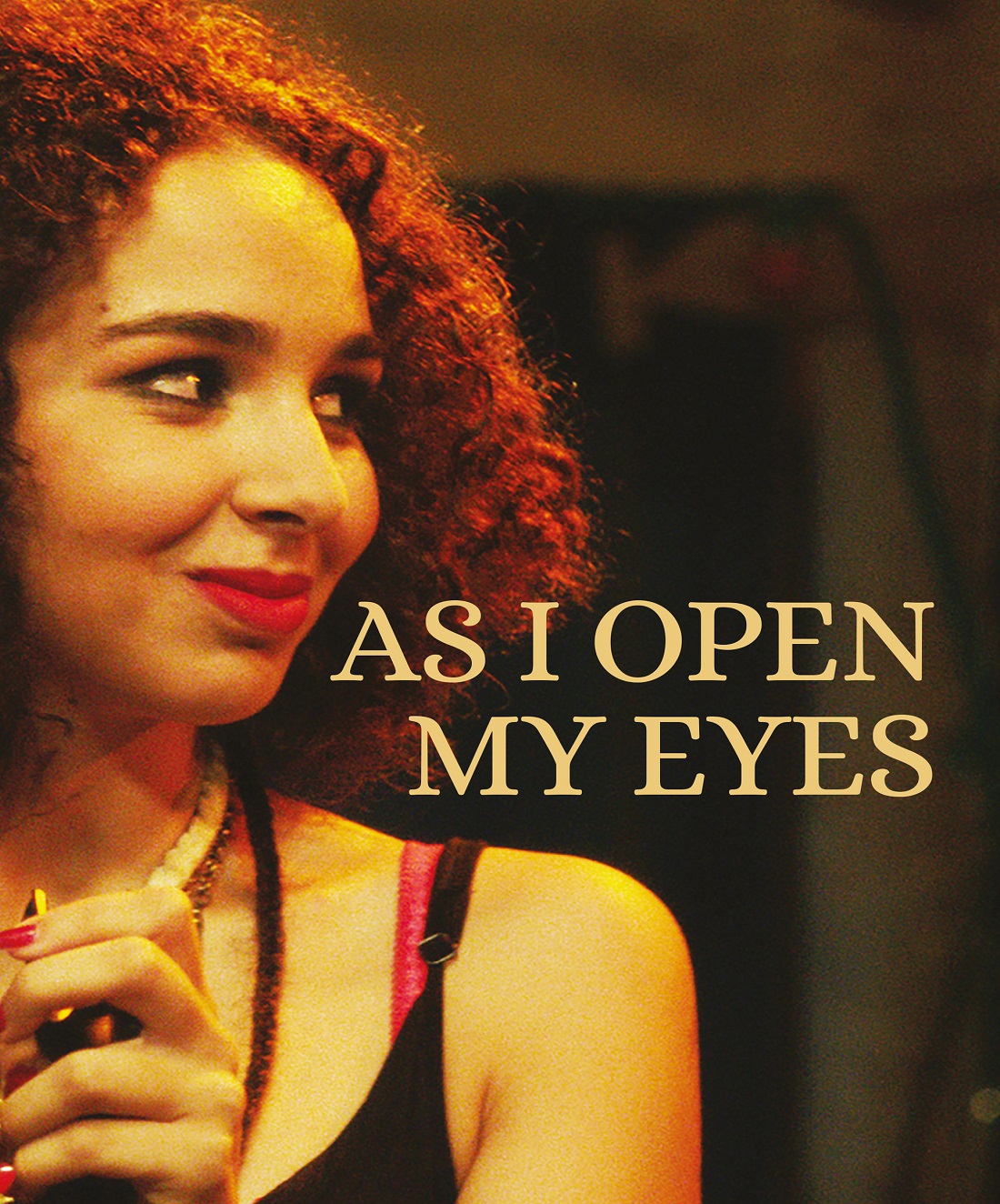

The character of Farah, played by Baya Medhaffar in her first major role, anchors the film in the immediacy of youth. At eighteen, Farah is not portrayed as an emblem or a symbol. She is impulsive, inconsistent, and often reckless. Her involvement in an underground rock band is not framed as heroic resistance but as an instinctive search for space. Music becomes her mode of articulation because other languages have failed her. The lyrics she sings are overtly political, yet the film’s attention remains on the act of singing itself, on breath, voice, and presence, rather than on rhetoric. Ten years on, this choice feels increasingly deliberate. Bouzid allows music to function as lived experience rather than message.

One of the film’s most enduring strengths lies in its portrayal of surveillance as something diffuse and internalized. The threat does not reside solely in police stations or interrogation rooms. It is embedded in conversations, in glances, in the caution practiced by parents and friends. Farah’s mother Hayet, portrayed by Ghalia Benali, embodies this complexity with remarkable precision. She is neither antagonist nor protector in any simple sense. Her fear is inherited, shaped by years of adaptation to an authoritarian environment. The conflict between mother and daughter unfolds not as generational opposition, but as a clash between survival strategies. Over the past decade, this relationship has only gained interpretive depth, especially in light of how post revolution realities complicated earlier hopes.

Visually, the film resists stylization that would distance it from its setting. Tunis is presented without postcard framing or exotic emphasis. Streets, apartments, cafés, and rehearsal spaces are shown as functional environments, shaped by use rather than symbolism. Cinematography remains close to bodies, often handheld, reinforcing the sense that the camera is embedded rather than observing from a position of authority. This proximity has helped the film endure beyond its initial political context. It feels less like a representation of Tunisia in 2010 than a record of how it felt to inhabit that time.

When As I Open My Eyes premiered at Venice Days in 2015, critics noted its restraint and precision, often highlighting its refusal to dramatize repression in overt terms. Over ten years, that restraint has proven to be its most durable quality. The film does not ask to be read as a revolutionary artifact, even though it is inseparable from the historical moment that followed. Instead, it documents the emotional and psychological conditions that made rupture imaginable, without claiming ownership over what came next.

In the broader landscape of Tunisian cinema, the film occupies a singular position. It does not belong entirely to the pre revolution era it depicts, nor does it align neatly with the post revolution wave that followed. Its production itself sits in between, shaped by memory, proximity, and a careful refusal of hindsight. This in between status is perhaps why the film continues to circulate internationally, in academic contexts, retrospectives, and discussions about youth, music, and political subjectivity. It does not resolve the questions it raises. It leaves them open.

Ten years on, As I Open My Eyes can be understood as a film about thresholds. Between adolescence and adulthood. Between expression and consequence. Between silence and speech. Its lasting importance does not come from prediction or representation, but from attention. Leyla Bouzid paid attention to gestures that history often overlooks, and in doing so, preserved a fragile moment that might otherwise have disappeared beneath the weight of what followed. That act of attention is what continues to give the film its quiet authority today.