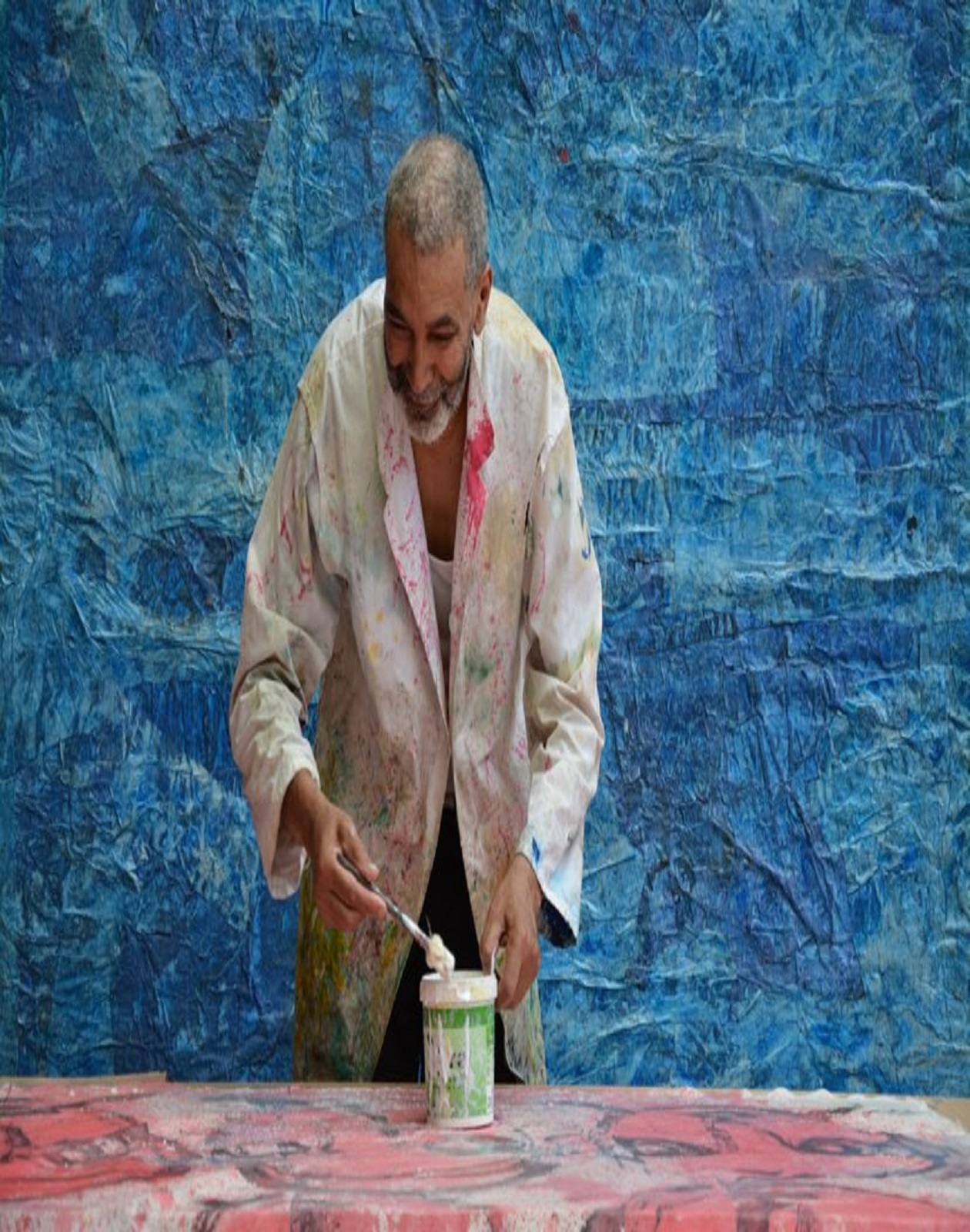

Hammadi Ben Saad (1948–2025)

On Friday, July 25, 2025, Hammadi Ben Saad, a major figure in contemporary Tunisian art, passed away at the age of 77. Known for his unique collage works and use of recycled materials, Ben Saad was a self-taught artist whose career spanned several decades and earned recognition both in Tunisia and internationally.

The Ministry of Cultural Affairs issued a brief communiqué expressing regret. But those who knew his work or knew him understood that this was more than the end of a career. It was the final brushstroke in the life of an artist who had spent nearly six decades carving out a space where memory, matter, and imagination could coexist.

He had no formal training. He didn’t come from a lineage of artists. And yet, from the moment he picked up a brush in the mid-1960s, Hammadi Ben Saad became one of the most daring visual storytellers Tunisia had ever produced.

He began, fittingly, as a teacher. Born in Tunis in 1948, Ben Saad spent his early professional years in public schools and community art clubs, animating workshops for children. But beneath the day job lived an insatiable creator, someone for whom art was not simply a form of expression but an act of survival.

By 1966, he had begun painting. And a decade later, in 1976, he exhibited for the first time. From the outset, it was clear: his work would not cater to market trends or academic styles. It would be messy, improvised, restless.

He wasn’t interested in mastery as defined by institutions. He was building a language. His own.

Ben Saad’s art came from the street, the souk, the Medina, from whatever he could get his hands on. Cardboard, kraft paper, old newspapers, rusty cans, torn fabric, glue. He piled them together, painted over them, scratched them, wounded them, and stitched them back together. The result wasn’t polished, but it pulsed with life.

His works were not trying to replicate the world. They were trying to remember it. He once described his own method as “layering the echoes of time.”

A three-year residency at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris from 1977 to 1980 deepened his approach. Later came a UNESCO internship in France and a Pro Helvetia grant in Switzerland. His wanderings took him across Europe, the United States, and Asia. But no matter how far he traveled, the inspiration remained grounded in Tunisia, in the dusty tones of the seasons, the noise of the Medina, the shadows of history.

His art was figurative when it needed to be. “Stacked heads,” masked portraits, elongated bodies, haunted and haunting. Sometimes his figures screamed. Sometimes they were silent, faceless. Other times, his canvases dissolved into abstraction: diffuse shapes, lines, monochromes. There was rhythm in the chaos.

In one phase, he drew endlessly on political newspapers. In another, he pierced and tore through surfaces, seeking new textures. Over time, his work evolved, but it never grew comfortable.

He called himself a vivid painter. Never naïve. Never decorative. He resisted the clean lines of contemporary galleries and the digestible aesthetic of biennials. To view his work was to enter a psychological space where texture mattered more than meaning and the act of making was itself the message.

In 2025, just weeks before his death, a major retrospective opened at TGM Gallery in La Marsa. Titled “Echoes of a Journey,” it offered a time-travel through his obsessions: crumpled paper, ghostly figures, bleeding colors, and surfaces that felt more like skin than canvas.

Visitors left unsettled, moved. Critics called it one of the most essential exhibitions of the year. No one knew then it would be his last. And yet, it felt like a farewell, a way of tracing his path without erasing the mystery.

Those who worked with him recall an intensely focused man, quiet, often smiling, but never seeking attention. He believed art was not a performance. It was a necessity.

He lived modestly. He didn’t chase collectors or court critics. And when asked what his art meant, he rarely gave a straight answer.

But in a rare quote, he said this:

“I require space to fully manifest my dreams and unleash my creative expression. This is how I am able to express myself at my utmost potential.”

That space, physical, emotional, spiritual, is what he demanded for himself. And in doing so, he opened a door for others to do the same.

Hammadi Ben Saad never fit neatly into any category. He was a maker, a poet in materials, a restless inventor. His legacy is not just in what he produced, but in how he lived: independently, experimentally, fiercely.

In Tunisia and beyond, he inspired generations of artists not by instructing them but by showing that you don’t need permission to create. You just need the will, the space, and the courage to tear the page and start again.