FAÏZA 1956

Not a slogan. Not a symbol. A name chosen with intent. In Arabic, Faïza means “the victorious one.” And when the first issue appeared in November 1959, just three years after independence, it marked not just the beginning of a magazine, but the beginning of a consciousness. The awakening of a woman long silenced, written out of history, now writing herself back in.

This is the story of Faïza. Not just the paper it was printed on, but the vision it carried. Not just who published it, but who read it and what it changed.

The Founders: Women Who Knew How to Begin

History remembers great revolutions. But it often forgets the hands that picked up the pen first.

Faïza was founded by Safia Farhat, a visionary Tunisian artist, educator, and reformer. She was not just the first woman to teach at Tunisia’s Institute of Fine Arts. She was the first to understand that art and media could be a form of liberation. In her eyes, a magazine was not a decorative object. It was a weapon.

Joining her in the mission was Dorra Bouzid, one of Tunisia’s earliest and most fearless women journalists. She had already shaken public discourse with her column Feminine Action in the nationalist press during the late 1950s. With Farhat’s artistic leadership and Bouzid’s editorial fire, Faïza was born at the intersection of creative expression and feminist urgency.

They didn’t shout. They printed.

They didn’t march. They published.

And they invited other women to do the same.

What Faïza Was, and What It Was Not

On the surface, Faïza looked like many women’s magazines of its time. It featured sections on beauty, fashion, home life, and parenting. But below the surface, it was something far more radical. It offered profiles of working women. It tackled questions of divorce, education, reproductive rights, and labor.

It created a space where a woman could see herself as both caregiver and citizen. As thinker and creator. As someone with a past to remember and a future to build.

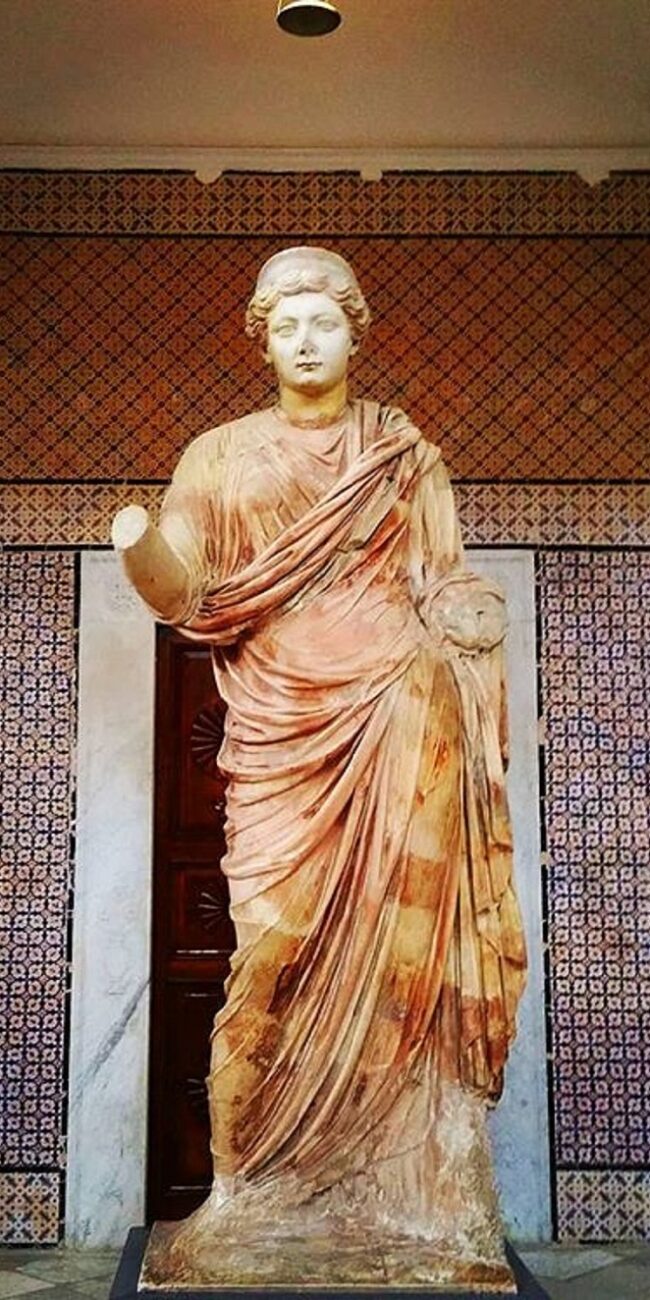

It was not a Western imitation. Nor was it a purely nationalist publication. Faïza was something rare: a Tunisian magazine that centered the woman not as a symbol, but as a subject. In her own voice. In her own body.

It was Tunisia writing itself with a feminine hand.

The Language of Covers and Pages

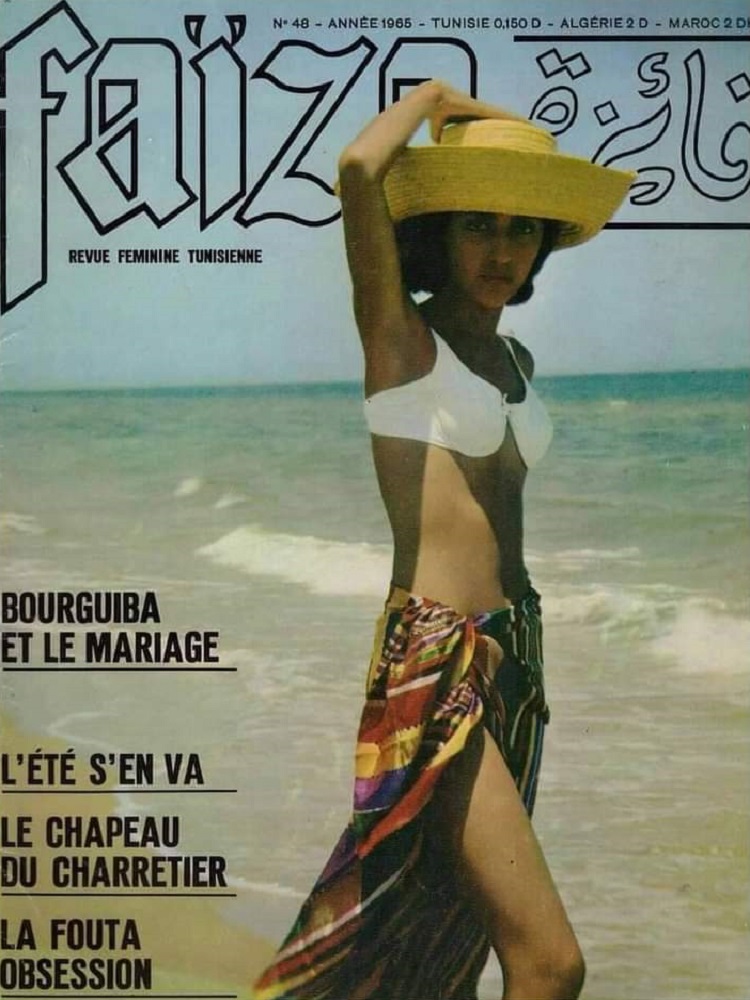

If radio was the voice of the new nation, Faïza was its mirror, quiet but present. Its covers often featured elegant Tunisian women dressed in both traditional and modern attire. One memorable issue from 1965 showed a woman wearing a swimsuit, topped with a fouta and straw hat, smiling under the summer sun. A striking visual message. Tradition and modernity could coexist. A Tunisian woman could be both modest and free, proud of her culture and unafraid of her presence.

Inside the pages, the magazine featured work by literary giants like Assia Djebar and Ali Douagi, as well as poetry from readers and essays by emerging Tunisian writers such as Zahra Ben Slimane, Sania Klibi, and Zahla Hanbalia. These names are not always remembered in literary history, but Faïza remembered them. Because they wrote not to be remembered, but to be heard.

Each issue carried this quiet insistence: Women are not an audience. They are authors of the moment.

A Magazine as Messenger of Bourguiba’s Feminism

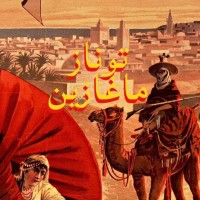

To understand Faïza, one must understand its context. Tunisia had just passed the groundbreaking Code of Personal Status in 1956, which abolished polygamy and granted women unprecedented legal rights in the Arab world.

President Habib Bourguiba envisioned women as pillars of the modern republic. But even he needed messengers. Faïza became one.

The magazine aligned itself with this vision of state feminism, conscious, secular, modern, and measured. But it never lost sight of the women themselves. It did not just echo policy. It filled in the human experience behind the law.

Where Bourguiba offered reform, Faïza offered reflection.

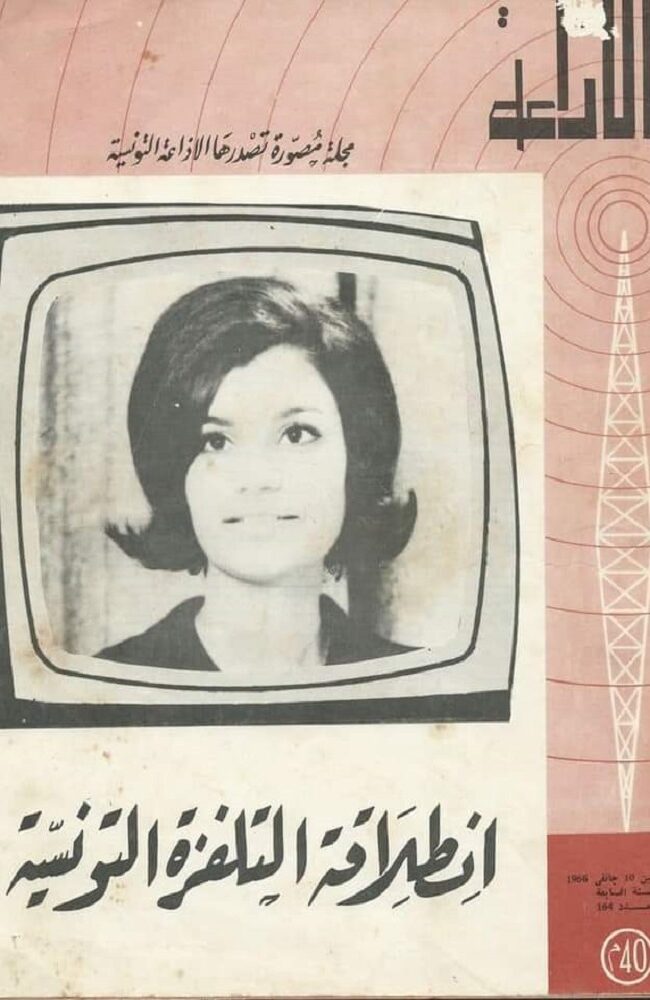

The Quiet End: A Signal Fades

In December 1967, Faïza published its final issue. There was no dramatic closure. No farewell editorial. Just silence. The kind that comes not from failure, but from exhaustion.

By then, Tunisia’s media landscape had changed. Other state publications began absorbing feminist narratives. Radio and television offered new platforms. Faïza, delicate, printed, slow, could not compete with the velocity of visual media.

But that ending was never really an end. Just a change of format. The generation that grew up reading Faïza would later become the very women who spoke on air, taught in schools, wrote in newspapers, and voted with confidence.

Because once the feminine word has been written, it never fully disappears.

Legacy: A Whisper That Shaped an Echo

Today, few Tunisians remember the details of Faïza. But its legacy lives in every woman who believes her voice matters. In every magazine or podcast or article that centers the lived experience of women. In every mother who tells her daughter that independence is her birthright.

Faïza was not only a magazine. It was a mirror of becoming. A thread between tradition and transformation. A notebook passed between sisters.

It told us that femininity and intellect were not opposites.

That beauty and protest could share a page.

That feminism, in Tunisia, had a face long before it had a name.