Broadcasting

Before the signal came the silence. Not the silence of peace or meditation, but a silence imposed by colonization, by decades of muffled tongues and censored ideas. In Tunisia under French rule, the spoken word was often filtered, measured, and redirected through foreign interests. The airwaves, those invisible carriers of voice and vision, were not yet the possession of the people. But when Tunisia claimed its independence in 1956, something subtle but profound began to shift. The silence was about to break.

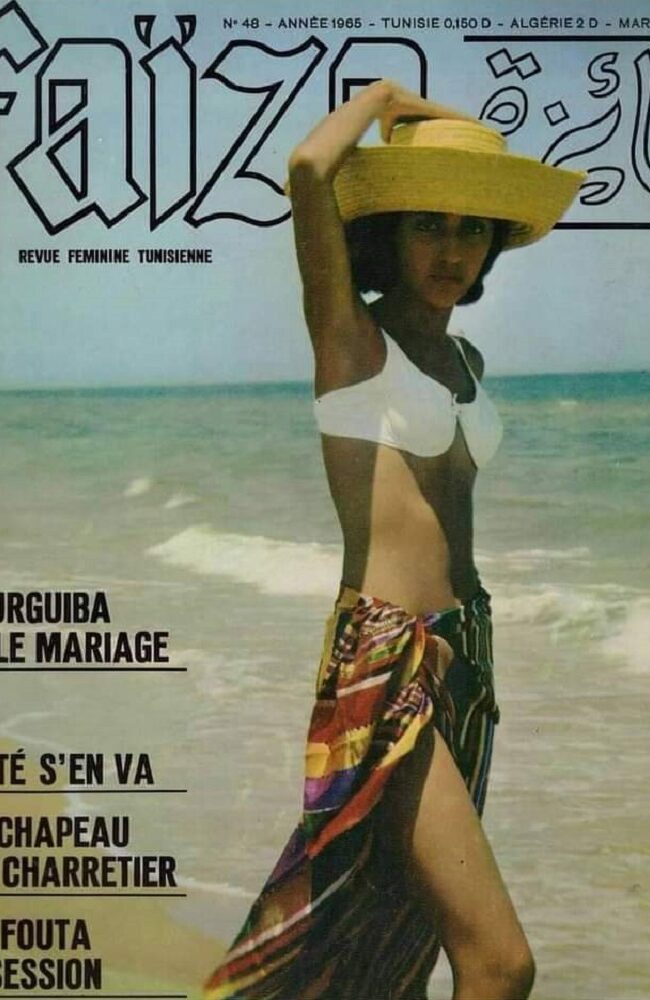

The 1960s in Tunisia were not just a decade of politics and policy. They were years of becoming. As the country charted its path under President Habib Bourguiba, broadcasting, radio first, then television, emerged as both a reflection and an instrument of the nation’s transformation. It was a time when Tunisians heard themselves in a new way, and for the first time, they saw themselves.

A Radio Revolution Rooted in the Past

While Tunisia’s official independence was declared in March 1956, the roots of its broadcasting infrastructure stretched further back. Radio Tunis, the country’s oldest broadcasting institution, began operating as early as October 15, 1938, under French colonial rule. At first, it broadcast in French and was designed to serve French settlers and colonial administrators. Only later did Arabic-language programming begin to take shape, slowly offering local listeners a sense of proximity to their own culture.

But it wasn’t until post-independence that radio became truly national, not only in language but in soul. Under the newly formed Établissement de la Radiodiffusion Télévision Tunisienne, radio was nationalized and restructured to reflect the country’s ambitions. Studios were upgraded, transmission expanded to the inland regions, and programming became increasingly diversified to include news, music, poetry readings, theater, and educational material.

The human voices behind these broadcasts became icons. Habib Chebil, with his sharp intellect and poetic tone, hosted cultural programs that bridged classical Arabic literature with modern thought. Ali Ben Ayed, already renowned as a theatrical actor, brought gravity and sensitivity to radio readings and news segments. His voice, unmistakably elegant, was said to calm the chaos in a man’s mind. These were not just presenters. They were companions. Their voices became familiar presences in homes across the country, traveling through transistor radios on market stalls, kitchen counters, and street cafés.

The Day Tunisia Saw Itself: Birth of Television

If radio was the voice of the nation, television was its mirror.

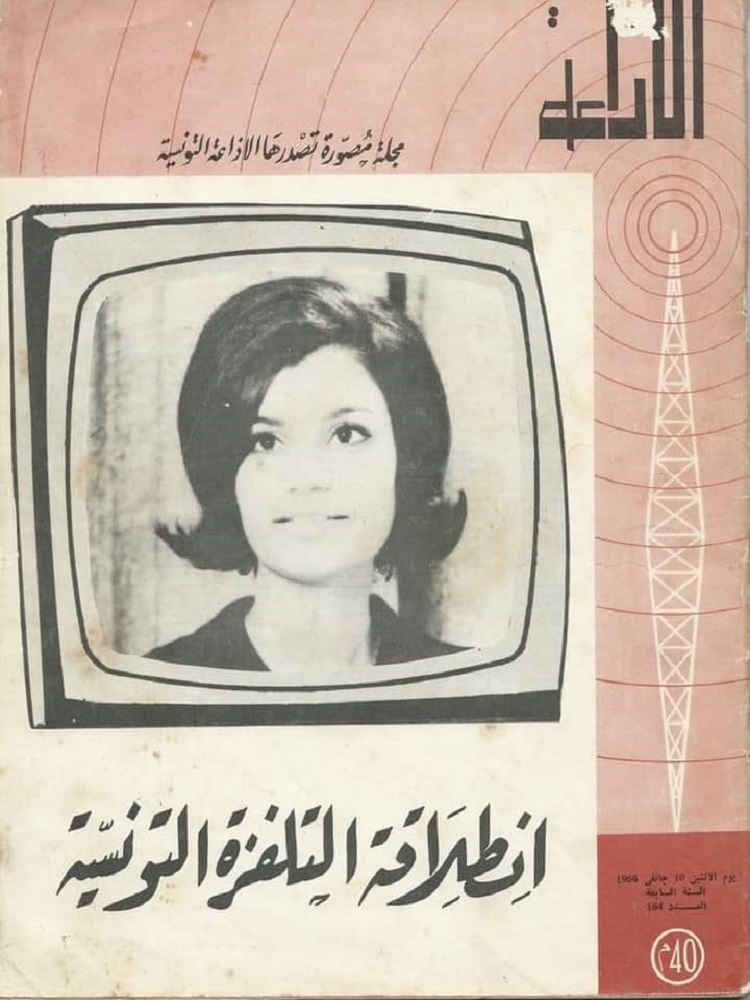

On October 31, 1966, Tunisia broadcast its first official television program. It was a carefully orchestrated affair, symbolic of more than just a technological leap. The first broadcast began with a brief opening ceremony and an address from government officials, followed by a cultural segment and news bulletin. Hamadi Ben Othman, a polished and articulate presenter, was among the very first faces to appear on screen. His confidence and composure helped the country accept this new and sometimes intimidating medium.

The transmission was modest, two hours of black-and-white programming available only in Tunis and a few nearby areas. But despite its limitations, the impact was enormous. For many, it was the first time seeing not Paris or Cairo on screen, but Tunisian faces, speaking Tunisian Arabic, discussing Tunisian issues. It was in essence the beginning of a new visual identity.

Zakia Bouzid, one of Tunisia’s first female television presenters, joined shortly after. Her presence was groundbreaking, not only for her gender, but for the warmth and intelligence she brought to each segment. She read the news, hosted talk shows, and became a symbol of the modern Tunisian woman Bourguiba was championing through his social reforms.

Broadcasting as a Tool for Nation Building

Broadcasting in 1960s Tunisia was deeply intertwined with the state’s vision of a modern, secular, and unified nation. President Bourguiba understood the power of media, not as entertainment, but as education, persuasion, and transformation. He used radio and television to deliver long, philosophical speeches about hygiene, education, birth control, women’s rights, and religious reform. These broadcasts were frequent and often mandatory for stations to air. They were not just political. They were almost liturgical.

This may seem heavy handed now, but for many Tunisians of the era, these broadcasts were a school. In villages where literacy was low, a family might learn about basic health practices or the importance of schooling not from a doctor or teacher, but from the evening radio program. Broadcasting became in many ways the public square of the new republic.

Of course, it was also a tool of control. Dissenting voices were largely excluded. The media landscape was carefully curated to ensure alignment with state policy. But within these confines, a great deal of creativity and cultural flourishing took place.

Music, Memory, and the Soul of the People

Music programs were some of the most beloved in both radio and television. Radio Tunis especially became a launchpad for artists such as Oulaya, Naâma, Hedi Jouini, and Ali Riahi. Their songs, broadcast daily, created a shared sonic experience across the country. Families gathered around their radios not just for news, but for music, music that blended Andalusian heritage with Egyptian influences and Tunisian authenticity.

These moments were deeply emotional. In a country still healing from colonization and searching for a national rhythm, a popular song could feel like a form of liberation.

On television, musical programming introduced viewers to orchestras, live concerts, and traditional folk music from various regions. It revived interest in mezoued, malouf, and stambeli. This was not just entertainment. It was cultural preservation through mass media.

The Humanity Behind the Machines

Behind every voice and every image were people. Producers, writers, sound engineers, cameramen, musicians, and announcers, many of whom learned by doing. In the 1960s, Tunisia had few trained media professionals. Much of the RTT staff were educated abroad or trained locally through workshops and hands-on experience. These were the unsung heroes of national broadcasting, working long hours with limited resources and enormous pressure.

Yet despite the odds, they created a broadcasting culture that was authentic, proud, and rooted in the everyday experiences of Tunisian life. Their legacy lives on in every program we take for granted today.

An Inherited Signal

To understand the Tunisian media landscape of today, with its diversity, its criticism, its satirical shows and political debates, we must return to the quiet tension of a 1960s living room, where a family huddled around a newly bought radio, or later, a flickering television set. Those early broadcasts were not perfect. But they were powerful.

They were the first breath of a country learning to speak in its own language, with its own image, about its own future.

In retrospect, broadcasting in 1960s Tunisia was not just the emergence of media. It was the emergence of self, an ongoing conversation between the country and its people, between memory and possibility.

And so, from silence to signal, Tunisia became more than a name on a map. It became a voice in the air.